Evidence traceability and minor textual blemishes: Onn and Lew

The following paragraph is taken from Lew (2025).1

馬六甲王朝時期,對華船採取禮遇政策,給予華船免稅優惠,僅以習慣性贈送價值5%之貨物即可,吸引了不少華船到來。葡萄牙文獻記載16世紀初,中國每年皆採購來自馬六甲至少十艘商船的胡椒,每年約有八至十艘的華船到來馬六甲。1511年,阿布奎 (Afonso de Albuquerque) 親征馬六甲時,即見五艘華船停泊在馬六甲港口,阿布奎並且與他們交談甚歡。這可謂是地理大發現以來,中西的第一次非官方接觸,這種接觸不在中國,亦不在西方,反而在馬六甲,正反映了15至16世紀初馬六甲海峽的重要性。 (安煥然 1998:291)2

There are a couple of small issues with Lew's treatment. It is true that during the earlier Malay administration, duties were not paid in money but in the form of gifts. However, the exact rate of these tribute-like payments is not consistent throughout the trade history. Lew's number is one of the two numerical example given by Pires, i.e. \(\frac{15}{300}\) ad valorem or 15 cruzados levied on every 300 cruzados's worth of merchandise). Moreover, as noted by Pires, the gifts presented by Chinese merchants were greater than those from all other regions, and the collection was further amplified by the sheer volume of goods traded by the Chinese in Melaka. The gift-duty policy is applicable to all nations from the East and not just China, as it is clear from the following passage from Pires3:

Todo Levamte nom pagua dirreitos das mercadarias, somemte presemtes ao rey e as pessoas nomeadas, scilicet, Pahão e todollos lugares atee China, todalas ilhas, Jaõao, Bamdam, Maluquo, Palimbão, e todos os da ilha de Çomotora. E os presemtes sam razoadamemte compridos, querem parecer dirreitos. Avia taxadores que orçavam ysto, se custumava geerallmemte, e os presemtes da Chiina erã mores que de todas partes, e estes presemtes releva gramdememte, porque hee gramde a comtia dos navegamtés que pagava presemtes. E se em Malaqua vemdiã juncos, emtam se pagava de dirreitos duas [ou] tres tumdaias d'ouro por casquo, e esto hé do rey de Malaqua. E despois se ordenou que de cada iiic cruzados se pagasem de dirreitos quymze cruzados, e ysto recadava os xabamdares das naçoes pera o rey. Todos mamtimetos pagã presemtes e nam dirreitos.

In the paragraph quoted by Lew, the tax incentive narrative is awkwardly intertwined with the story of the five Chinese junks, as it fails to properly account for the background of the interaction between the Lion of the Seas and the Chinese merchants.

The fact is, prior to their cordial exchange 交談甚歡 with Afonso de Albuquerque, the Chinese merchants had been detained by Sultan Mahmud. In retaliation for the robbery and tyranny they had endured under his rule, they voluntarily offered their support for the Portuguese campaign to conquer Malacca. However, Afonso de Albuquerque declined their offer. The treatment received by the Chinese merchants in 1511 thus stands in stark contrast to the policy of courtesy 禮遇政策 highlighted in the opening statements of Onn (1998) and Lew (2025).

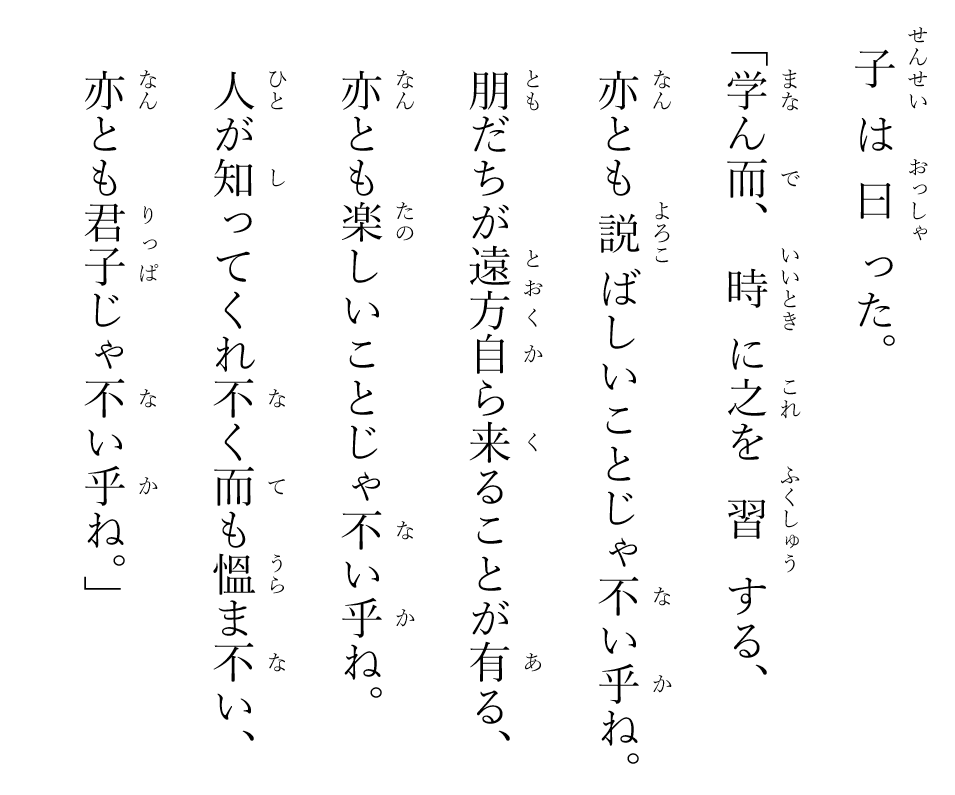

- Lew Bon Hoi 廖文輝 (2025) A history Malaysian Chinese 馬來西亞華人史, SIRD, Petaling Jaya. Lew's paragraph is approximately:

During the Malacca Sultanate period, a policy of courtesy was adopted toward Chinese ships. These ships were granted tax exemptions and only needed to offer, as a customary gift, goods worth 5% of their cargo’s value. This attracted many Chinese ships to visit. According to Portuguese records, in the early 16th century, China annually purchased pepper from at least ten merchant ships originating from Malacca, and each year around eight to ten Chinese ships arrived in Malacca.

In 1511, when Afonso de Albuquerque led an expedition to Malacca, he saw five Chinese ships anchored at the port of Malacca and had pleasant conversations with their crews. This can be regarded as the first unofficial contact between China and the West since the Age of Discovery. Interestingly, this contact did not take place in China or the West, but rather in Malacca—highlighting the strategic importance of the Malacca Strait in the late 15th to early 16th century.

- Onn Huann Jan 安焕然 (1998) Pre-independence Chinese economy 獨立前華人經濟 in 林水檺、何啟良、何國忠、賴觀福 (1998) A New History of the Chinese in Malaysia (Volume 2) 馬來西亞華人史新編・第二冊, 馬來西亞中華大會堂總會, 吉隆坡, pp. 289 - 323.

Lew reproduced most of the words in Onn (1998, p. 291):

15世紀之時,馬六甲王朝即對華船採取禮遇政策,華船到來,給予免稅之優惠,僅以習慣性贈送值5%船貨之物即可4,因而吸引了相當多華船的到來。據葡萄牙的文獻,16世紀初中國市場的需求,每年欲購買來自馬六甲至少10艘的商船所載的胡椒量,而且每年約有8至10艘的華船到來馬六甲。5

1511年葡萄牙阿布奎 (Afonso de Albuquerque) 親征馬六甲時,即見有5艘華船停泊在馬六甲港。阿布奎並且與他們交談甚歡。這可謂是西方人「地理大發現」後,中西的第一次(非官方)接觸。這中西勢力第一次的接觸是頗具意義的,它既不在中國,亦不在西方,反而是在馬六甲,正反映了15至16世紀初中國民間海貿活動在馬六甲之頻繁景象。6

Dr. Onn explained to me that he did not use the English or the Portuguese text of Pires. Instead he relied on a Chinese translation and a paper by Zhang (1988). See Tome Pires 托梅・皮雷斯 (1988):Suma Oriental 1515年葡萄牙人筆下的中國,in《中外關係史譯叢・第四輯》, 上海譯文出版社, Shanghai 上海, p. 284 and Zhang Zengxin 張增信 (1988) Maritime Activities in Southeast China during the Late Ming Period (Volume 1) 明季東南中國在海上活動・上編, 東吳大學中國學術著作獎助委員會, 台北, p. 198.

- Rui Manuel Loureiro (2017) Suma Oriental de Tomé Pires, Centro Científico e Cultural de Macau, Lisboa.

Pires's description can be translated as: All people from the East do not pay duties on their merchandise, only gifts to the king and certain designated persons. These Eastern countries were Pahang and all coastal ports leading up to China, all the islands, Japan, Banda, Moluccas, Palembang, and all those from the island of Sumatra. And these gifts are reasonably generous, and they are considered as duties. There were appraisers who estimated their value, and this was the general custom. The gifts from China were greater than those from all other places, and these gifts were significant, because the number of navigators who paid gifts was large. And if junks were sold in Malacca, then duties were paid of 2 or 3 tumdayas of gold for every ship sold in Melaka, and this belonged to the king of Malacca. Later, it was ordered that for every 300 cruzados of merchandise, 15 cruzados in duties were to be paid, and this was collected by the Shahbandars of the various nations for the king. All foreigners paid gifts, not duties.

Comments