Whoever says Industrial Revolution says cotton

The East India Company, established in 1600, was founded to capitalize on the early waves of globalization initiated about a century earlier by Iberian explorers. By the 1660s, the Company had begun shipping cotton textiles from a key port on the Malabar Coast. The orthographically correct spelling of the name of the port is Kozhikode (Malayalam: കോഴിക്കോട്), though the phonetically correct way to handle the word is Kōḻikkōṭu. The British anglicized the toponym to Calicut, and over time, began referring to the cotton fabrics imported from there as calicoes, naming them after the city itself, much like how Muslins from Dhaka came to be known as Bengals.

Unlike wool and linen, calico was made from cotton, which was softer, lighter, and more breathable. British markets soon became flooded with cheap calicoes, which posed serious competition to local textile producers. These imported fabrics were relatively inexpensive largely because of lower wages in India. As a result, domestic textile industries came under intense pressure, prompting the English Parliament to pass legislations aimed at restricting Indic textile imports to protect the local wool and linen manufacturers.

The Calico Acts, while intended to protect local wool and linen industries, also helped lay the fertile ground for the growth of the cotton industry in Lancashire. Initially, the British imitated Indian methods of cotton spinning and weaving, carrying out these tasks through domestic, manual labor. However, faced with relatively high wages, there was growing pressure to improve efficiency. This led to a wave of automations and introduction of a myriad of mechanized unit operations aimed at optimizing the cotton manufacturing process.

In 1764, James Hargreaves (b. 1720, d. 1778) developed the spinning jenny, allowing multiple spools of thread to be spun at once. By 1769, Richard Arkwright (b. 1732, d. 1792) patented the water frame, two years later, he established the first large-scale mechanized spinning factory in Cromford. Then in 1779, Samuel Crompton (b. 1753, d. 1827) completed the integration of the best features of earlier machines. Crompton's spinning mule was a breakthrough that significantly advanced textile production. In 1781, steam engines were adapted for use in textile mills and water-powered frames were slowly phased out.

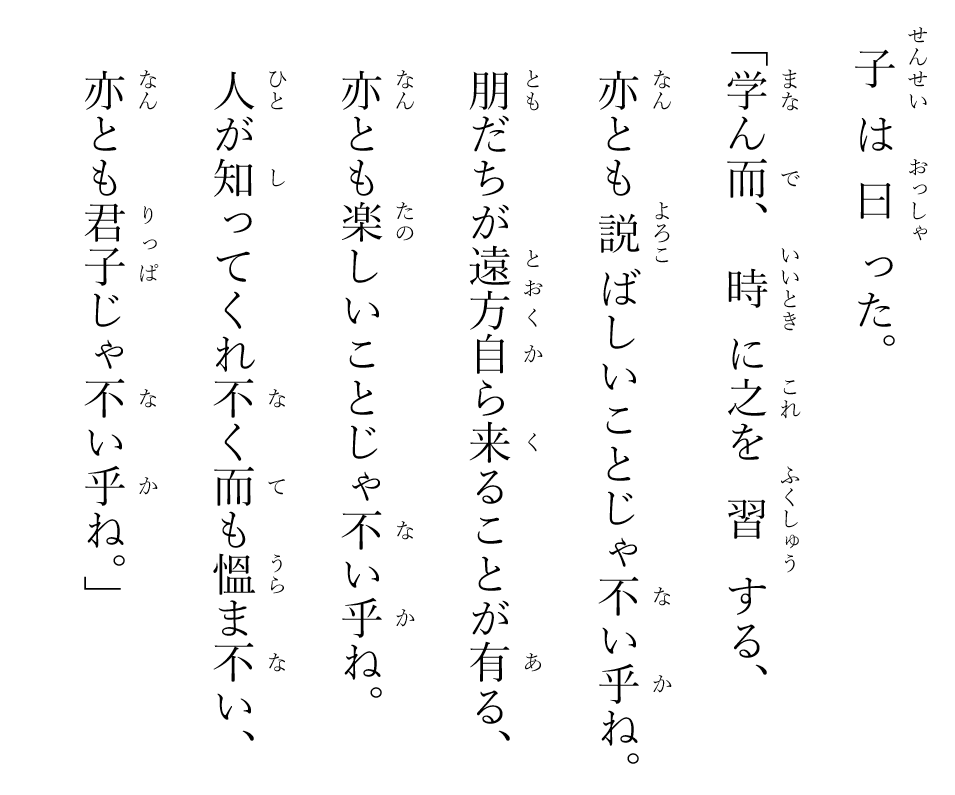

- . . . whoever says Industrial Revolution says cotton. When we think of it we see, like the contemporary foreign visitors to Engliand, the new and revolutionary city of Manchester, which multiplied tenfold in size between 1760 and 1830 (from 17,000 to 180,000 inhabitants), where ‘we observe hundreds of five- and six-storied factories, each with a towering chimney by its side, which exhales black coal vapour'; which proverbially thought today what England would think tomorrow, and gave its name to the schoold of liberal economics that dominated the world . . . See Eric Hobsbawm (1969) Industry and empire: from 1750 to the present day, Penguin Books, Harmondworth, p. 56.

Loomstate calico, it has a plain weave an natural cream color. It can be readily made into undergarments or serve as the base for dyeing and printing.

The spindle (\(n = 1\)) is placed horizontally in the Indic chakra, a design optimized for a spinner seated on the floor facing the machine.

A chinese spinning wheel with five horizontal spindles (\(n = 5\)).

- Calico 印花布 is a type of plain weave textile made from cotton. In Japan, calico was introduced by Portuguese and it was known as saraça (from Gujerati saras સરસ) or sarasa 更紗. The word was originally a reference to the city, but later as a reference to the textile product imported from Calicut, e.g. in Peter Heylyn's Cosmography (1666) p. 202: . . . and noted for the best Calicuts (a kind of linnen cloath so called from the City of Calicut, where it was first made), not to be matched in all the Indies . . .

- Initially, the Hargreaves's spinning jenny was fitted with 8 spindles, enabling parallel processing of eight strands of yarns with one ATP-powered wheel. Eventually the number of spindles was increased to 120. Arkwright's water frame was also a multi-thread machine, but it was powered by gravity since it employs water to turn the wheel. Early water frame can handle 32 threads simultaneously, but eventually the number is optimized to 128.

- The Calico Acts (1700, 1721) were acts of the Parliament of England and the Parliament of Great Britain which banned the import of most cotton textiles into England, followed by the restriction of sale of most cotton textiles. The first law required that from Michaelmas 1701 (29 September 1701), all wrought silks, Bengals and stuffs, mixed with silk or herba, of the manufacture of Persia, China or East India; and also all printed calicoes, and all painted, dyed or stained there, shall be locked up in warehouses appointed by the commissioners of the customs, till re-exported; so none of the said goods should be worn or used, in either apparel or furniture, in England, on forfeiture thereof, and also of two hundred pound penalty on th persons having or selling any of them. The second law is a law enacted to preserve and encourage the woollen and silk manufactures of this kingdom, and for more effectual employing the poor, by prohibiting the use and wear of all printed, painted, stained or dyed callicoes in apparel, household stuff, furniture, or otherwise, after the twenty fifth Day of December one thousand seven hundred and twenty two (25 December 1721).

- When Proton was introduced in 1985, its price was about 20% lower lower than that of Toyota and Nissan (of the same specifications). The 1.3-liter non-metalic model without air-conditioning was $16,047.62 (on the road without insurance, insurance was approximately $600), the same model with air-conditioning was $17,547.62, while the same model with full specifications was $18,667.62 (optional items: metallic paint = $300, air-conditioner = $1,500, radio/cassette player = $820). Nissan Sunny 130Y was priced at $23,247.95 (but Tan Chong offered to sell the unit at $19,500 in their anniversary promotion for a limited time). Toyota Corolla LE 1.3 was priced at $22,834.46. It goes without saying that the budget-friendly Proton Saga impacted the sales of competing cars. For instance, a Datsun branch manager attributed his disappointing November 1985 sales figures to Proton, stating that while he previously sold around 60 units, he managed to sell only 10 that month.

Comments