The lumpur and fowl of Hsü and Tsou

Part 1. Hsü Yün-Ts‘iao, Tsou Pao-Chün, and their Malay dictionaries

Hsü Yün-Ts‘iao 許雲樵 (1905 — 1981) was an Associate Professor and the Director of South Seas Researches 南洋研究室主任 in Nanyang University 南洋大學 (or Nantah) between 1957 and Hsü left Nantah in February 1962 and founded the Southeast Asian Research Centre 新加坡東南亞硏究所 (which is his new home office and library in 167 MacPherson Road, 3rd Floor).

The inaugural issue of a new journal (Journal of Southeast Asian Researches 東南亞硏究) by the Southeast Asian Research Centre 新加坡東南亞硏究所 was published in December 1965, and the last issue (volume 7) was published in 1971.

Actually Hsü had earlier in 1958 endured the South Seas Society 南洋學會 leadership coup masterminded by Peng Song Toh 彭松濤 (assisted by Lin Woling 林我鈴).

Hsü was the editor of the Journal of South Seas Society in 1940 - 1941, 1947 - 1957, but he was replaced by Wang Gungwu in 1958 (r. 1958 - 1961), and Wong Lin Ken in 1962. Hsü kept his position as a committee member of the society until 1967.

Eventually Hsü was offered a teaching role (r. 1964 - 1968) again in Ngee Ann College when the school was established.

See L. Seah (2007) Hybridity, globalization, and the creation of a Nanyang identity: The South Seas Society in Singapore, 1940 - 1958, Journal of the South Seas Society 61, pp. 134 - 151.1962.

In the second half of 1960, Hsü was offered to host a 15-minute podcast at Radio Singapura. The materials presented in the radio show was then edited (He wrote the preface of his book in Nanyang University (南洋研究室) on 17 May 1961, two weeks after the podcast series was concluded.

The book was published on 1 December 1961.17 May 1961) into a book titled: Mǎláiyà cóngtán 馬來亞叢談 Collected writings on Malaya, and it was published in 1961 in Singapore.

| No. | Podcast title | Date |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 太古時代的馬來亞 | 3 August 1960 |

| 2 | ⋮ | 10 August 1960 |

| 3 | ⋮ | 17 August 1960 |

| 4 | 馬來亞地名掌故談 | 24 August 1960 |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ |

| 40 | 新加坡的街頭文學 | 3 May 1961 |

In Chapter 4 (Mǎláiyà dìmíng zhǎnggù tán 馬來亞地名掌故談 On the historical origin of Malayan place names), we were told by Hsü that:

馬來亞的首都吉隆坡,這個地名也有問題,它並不是原名 Kuala Lumpur 的譯音,而是一個歷史陳迹。原來在一百年前葉德來開辟那里的時候,那時還是一個山芭,來往的華人,大多是在附近開采錫矿的客家矿工,那時他們稱吉隆坡為 Klang,客家人寫起字來,便作吉隆,后來那里熱闹起來,他們便給它加上一個坡字。 其實就是埠字訛別。但現在,吉隆坡已不再叫 Klang,卻把它讓渡給予巴生了。所以巴生也不是 Klang 的對音,而是馬來人稱市區中的一個地方叫做 Pasang,而被華人訛作全市的名稱。

Hsü correctly pointed out that 吉隆坡 is a not a direct translation of Kuala Lumpur and was able to reconstruct the term from 吉隆 (Hakka transliteration of the Malay toponym Klang) and 坡 (pura or town, i.e. similar to how 新加坡 = Singa + pura was assembled from its Malay components).

After the initial successful phonetic of isolation 吉隆坡 and Kuala Lumpur, Hsü went on to boldly assert that the Lumpur was a Chinese word loaned to the Malays and its original form was 濫巴 (lampa).

至於Kuala Lumpur也不是一個筒單的地名,因為這兩個字,並非純粹馬來語詞,前一個字我們知道是河口的意思,因為最初的市區是在 Gombak 河流入巴生河的地方,但這河口為什麼不叫 Kuala Gombak 而叫 Kuala Lumpur 呢?因為當時河口是一片濫巴 (Lampa),Lumpur 就是濫巴的譯音,所以在馬來文字典內是找不到 Lumpur 這個字的。

It is puzzling why Hsü was not able to locate 找不到 the word ‘Lumpur' with his Malay dictionaries. Hsü's bold assertion was obviously wrong and one can show this very easily by producing an actual dictionary entry for the word.

Unfortunately, Hsü's Lumpur theory was Tsou Pao-Chün 鄒豹君 (1967) Urban landscape of Kuala Lumpur, Insitute of Southeast Asia, Nanyang University, Singapore.

Tsou was trained (1929 - 1933) in Geography at Beijing Normal University 北京師範大學. Later, he did his Master degree in Geography at University of Liverpool (1937 - 1939). He was a Professor in Nanyang University from 1959 to 1969.

When the Dean of the College of Arts, Zhāng Tiānzé 張天澤 (r. 1956 - 1959), left in August 1959, Tsou was asked to temporarily hold the chair of Zhang until Yán Yuánzhāng 嚴元章 (r. 1960 - 1963). Tsou was again asked to deputize the role of the dean in 1968 - 1969.

Between 1960 - 1961, Tsou was in the Department of Historical Geography and one of his colleagues was Hsü.

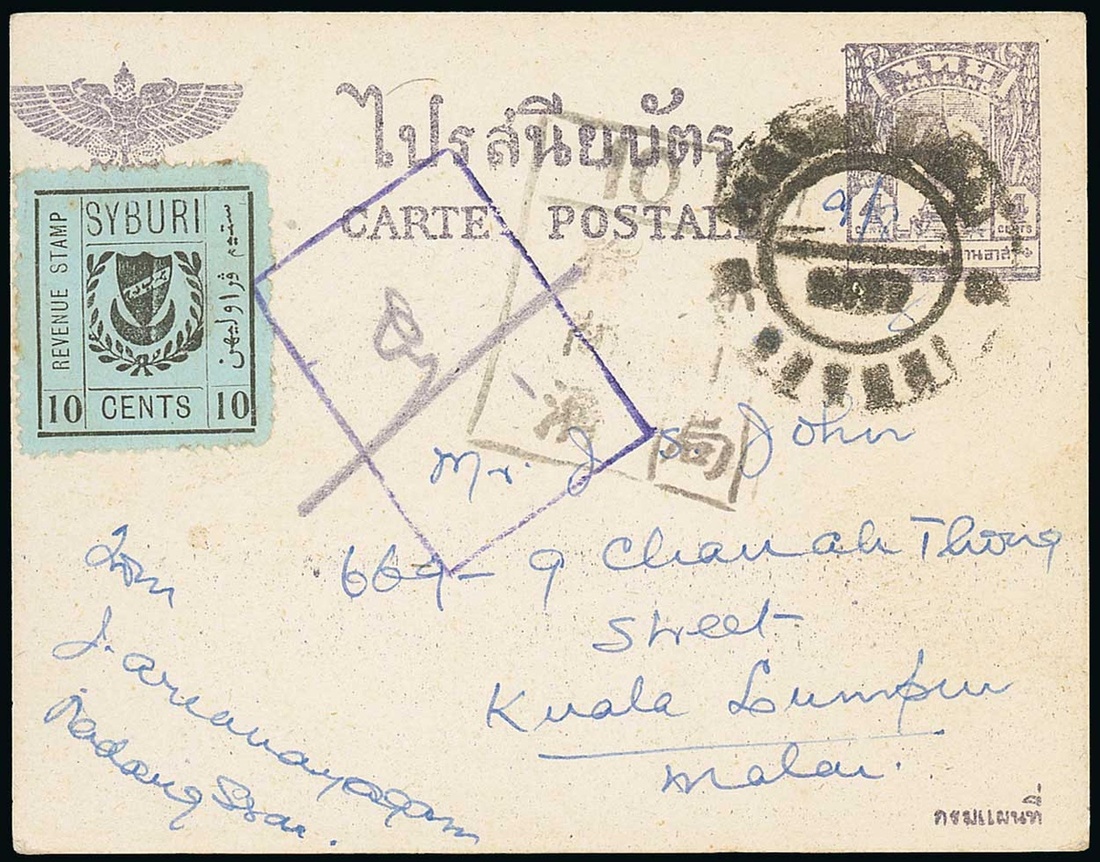

On 7 May 2024, I ordered my copy of Tsou's work from Hanshan Tang 寒山堂, London. Remarkably, it turns out to be the very copy that Tsou gifted to the Chinese archaeologist named Chêng Tê-k'un 鄭德坤 (1907 - 2001). I am aware that a copy of Tsou's work is available at the Za'ba Library, University of Malaya. Unfortunately, Za'ba Library is only open on non-weekends.repeated by Tsou Pao-Chün 鄒豹君 (1906 — 1993). However, Tsou adjusted the tone of the theory by positing that the word was introduced into the Malay lexicon only very recently.

. . . the second word, Lumpur, is according to the present usage, a Malay word too, but one hundred years ago it orginated from the Cantonese dialect. In that it means a flooded jungle 濫芭 or a decayed jungle 爛芭 . . .

The fact that lumpur can be found in Marsden's dictionary (1812) invalidated Tsou's claim that the word was culturally diffused from Cantonese to Malay about 100 years ago (circa 1860s, i.e. around the time when Malay population in Kuala Lumpur started to witness influx of Chinese miners). The linguistic and geological inferences in Tsou's paper (1967) were mercilessly dismantled by Lubis (2018), and was included by Lubis in his book to amuse his readers.

In p. 14, Tsou wrote:

. . . Among the Chinese Kelang Lumpur may have been corrupted to Ke-Lumpur 吉隆坡, who means ‘The following note was appended superciliously (in pp. 31 - 32) by the 62-year-old Tsou for ‘lucky prosperous slope':

When a poorly educated Chinese does not know how to write the Chinese characters of a given name correctly, he is apt to write the Chinese characters of the same pronounciation which, of course, have a different meaning. When he has an opportunity to change the incorrect characters of the given name, he will ask a well educated Chinese to choose for him the correct characters.

For instance, Ampang in the east of Kuala Lumpur has been translated into Chinese as àn-bāng 暗邦 (dark terrain) by poorly educated local Chinese. The name àn-bāng 暗邦 has been used for many years. Recently, àn-bāng 暗邦 has been retranslated into Chinese as ān-bang 安邦 (peaceful terrain or a safe terrain) by the well educated Chinese. It is quite possible that ‘Ke-Lum-Pur' 吉隆坡 (lucky prosperous slope) originated in the same way after the Civil War.

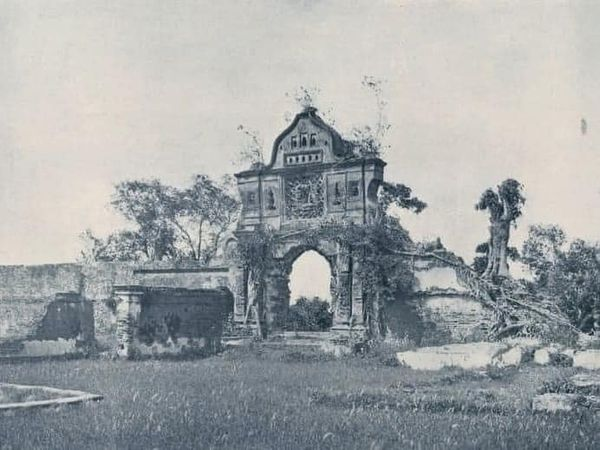

Tsou's limited knowledge in Malay words is glaringly visible here but he had the audacity to regard Malay-literate Huizhou Chinese who transliteratedampang (Malay word for dam) to àn-bāng 暗邦 as ‘poorly-educated Chinese'. a lucky prosperous slope' or ‘a happy, prosperous area of rising or falling ground'. In the author's opinion, the Chinese name Ke-Lum-Pur 吉隆坡 came into usage by the Cantonese and Hakka in the period of rehabilitation of Kuala Lumpur (1873 - 1875). They started to rebuild the ruined settlement in the hope that the area of Kuala Lumpur would be shortly restored to prosperity as before the Civil War; at the same time, they hoped that the place of the present Kuala Lumpur would be a happy land of rising and falling terrain. So they renamed the place of the present Kuala Lumpur Ke-Lum-Pur. According to the legend, the people who hated Yap Ah Loy twisted the name Ke-Lum-Pur 吉隆坡 to Ke-Lum-Pur 雞籠坡 (a land of basket for fowls). It is the considered opinion of this author that the name Ke-Lum-Pur 吉隆坡 was probably adopted in the period 1873 - 1879.

Tsou's theory was succinctly summarized in p. 15 (given below) and it shows that the human brains (like modern LLMs) can be easily induced to hallucinate by bias or incomplete datasets.

| Before 1857 | 1857 to 1873 | 1873 to 1875 | |

| Kelang or Klang 吉隆 | Lam-Pa 濫芭 | Kelang Lam-Pa or Klang Lam-Pa 吉隆濫芭 | Ke-Lum-Pur 吉隆坡 |

Part 2. Lampa and chicken theories, extension by modern Chinese authors

The lampa 濫巴 theory of Hsü (1960) and the chicken basket 雞籠 legend in Tsou (1967) were given different treatments by Looi (2021) in his essay titled ‘A land of basket for fowls 雞籠坡或吉隆坡'. Like most Malay-literate Chinese, Looi's view is that Hsü's lampa theory is apparently incorrect since ‘lumpur' is not Chinese word loaned to the Malays.

Looi claimed that (a) the early Hakka and Cantonese would sometimes refer to Kuala Lumpur with 雞籠坡 (

老一輩吉隆坡人都知道,早年客家人與廣東人又稱吉隆坡作雞籠坡。通曉華民方言的英殖民官員菲爾斯通 (H. W. Firmstone),1905年發表英屬馬來半島中英文地名錄,證實了吉隆坡確曾有雞籠坡這個說法:我也經常聽聞人稱kai-lam-po或ka-lam-po。

Since Firmware's original remarks was simply

I have also often heard -lam-po

and did not specifically supplied 雞籠坡 as the Chinese glyphs in his paper, Looi's claim that the Chinese Protector confirmed (證實吉隆坡確曾有雞籠坡這個說法) that 雞籠坡 was an alternate name for Kuala Lumpur is not entirely consistent with Firmware's original statement.

| Glyph | Mandarin | Quanzhou | Huiyang | Guangzhou |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 雞 | jī | guei1 | gai1 | gai1 |

| 吉 | jí | giat7 | git5 | gat1 |

| 籠 | lóng | long2 | lung1 | lung4 |

| 隆 | lóng | long2 | lung2 | lung4 |

| 冷 | lěng | ling3 | lang1 | lang5 |

| 坡 | pō | pou1 | bo1 | bo1 |

The alternate pronunication cited by Firmstone is likely used by a Ideally the word 隆 is to be pronounced as liong2 or long2 in Hokkien, but for the case of 吉隆坡, it is usually parsed as ka-lam-po by Hokkien speakers. It is likely because the old toponym 加冷埠 (Klang + po) is used or pronounced.

吉冷 Klang کلڠ or 加冷 Kallang کالڠ is a subgroup of Orang Laut. Both the Kallang River in Singapore and the Klang River in Selangor are named after this important sea nomad group since the Melaka period.

The phonem change from 冷 (laŋ) to 隆 (loŋ) was not fully appreciated by Chinese outside Selangor, and the phonetic handling was frozen at 冷 (laŋ | lam).speakers who phonetically parsed the word 隆 (loŋ) as 冷 (laŋ) since the 吉冷 was older transcription of

Tsou's position that a chicken basket 雞籠 story was invented by haters of Captain Yap Ah Loy 葉德來 is unlikely to be correct if we take Looi's observations seriously. It is probable that gai1lung1 雞籠 is another Looi's position is that gai1lung1 雞籠 is a descendant of git5lung2 吉隆 is suggested based a correct Mandarin-Hakka consonant swap pattern but this phonem swap cannot be used to correctly explain phonetic relationship between the two names, since (雞 gai1 ≠ git5 吉 in Hakka) or (雞 gai1 ≠ gat1 吉 in Cantonese).phonetic descendant of the Malay word ‘Klang' and it is equally old as the toponym git5lang1 吉冷. Note that however, gai1lung1 雞籠 describes only the phonetic value of

. . . as the history of the earth is written in the strata which compose its crust, and the life history of all animals in their structure and habits of life, so the history of a country is written in the names of its places. They are all fascinating studies, with just enough of uncertainty in drawing conclusions, to ally them with rubber option dealings . . .

Part 3. Phonetic chicken in Kedah

Tai Choon Thow 戴春桃 (1828? - 1922), of Huizhou descent, was the third Captain China in Alor Star. His full title was

Reyno de Malaca de hũa parte confina com o rey de Queda, & da outra cõ o reyno de Pam: & téra de comprido cem légoas de costa, & delargo pela terra dentro até hũa serra por onde parte o reyno de Sião, tera dez légoas . . . & aueria nouẽta annos pouco mais ou menos (quãdo Afonso Dalboquerq̃ ali chegou) q̃ era reyno sobre si, & vieram os Reis deste reyno a ser tam poderosos . . .

(The kingdom of Melaka on one side borders the kingdom of Kedah, and on the other the kingdom of Pahang. It has coastal length of about 100 leagues, and a width inland up to a mountain range where it borders the kingdom of Siam . . . And it had been 90 years, more or less, when Afonso D'albuquerque arrived there, that it was a kingdom on its own, and the kings of this kingdom became so powerful . . . ).

100 leagues is approximately 500 kilometers. Also, note the lower calendrical bound of the inception of Melaka, as given by Albuquerque, was 1511 minus 90 ≈ 1421.Negeri Qdḥ

One cannot help but notice that the name of the state is orthographically different from the For example, in R. J. Wilkinson (1901), p. 508, the dictionary entry for kĕdah' reads: I.

This archaic spelling is a strong clue that the word is of Arabic origin and the following observations by D. Perret (2014)

. . . Pengkalan Bujang may be home to one of several sectors, among the densest, if not the densest, in ancient glass-shard deposits for the whole of Southeast Asian. Only further excavation can help to determine the real extent of these deposits, and thereby provide clues to explain their presence with greater certainty . . .

suggests that Kedah was once an important marketplace for glassware, and hence the name

Looi (2022) repeated the application of the Applied earlier on 吉隆/雞籠 j-to-(k|g) switch when we move from Mandarin to Hakka/Cantoneseconsonant switch theory on Kedah

. . . 所以kit或gat便轉音為kai或gai,如州名吉打,客、粵語亦轉音成kai-da或gai-da,雞打也 . . .

Again, a simpler and more realistic way to explain the origin of 雞打 (Kai-da) is to seed the transliteration process with the original Malay name of the placename. It is interesting to note that, according to Xu and Gao (1928), the use of 雞打 (Gai-da) predates that of its modern form of 吉打 (Git-da).

Comments