Nocturnal sarabha in the Fansur-Lamri region

Between 900 and 953, Captain Buzurg ibn Shahriyar, a Persian shipmaster, compiled a collection of sailors’ tales, and among them appears a curious creature named zarāfah زرافة in the story of Lamri لامری (present day Aceh, North Sumatra).

For the uninitiated, zarāfah may seem easily identifiable as a giraffe. But a closer reading of ibn Shahriyar’s account quickly reveals a mismatch: the tame diurnal animal bears little resemblance to the beast described in the text. Instead, the creature in question more plausibly corresponds to the Sumatran rhinoceros.

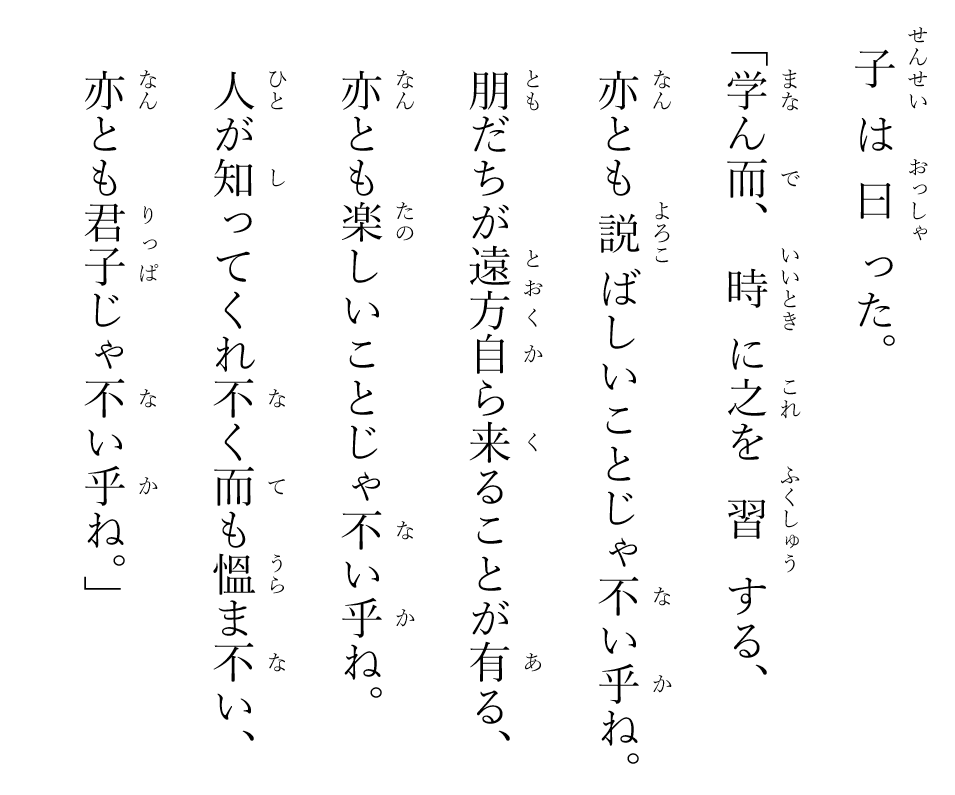

The following Persian text can be found in a French translation published in 1883:

وحدثنی أن بجزیره لامری من الزرافة ما لا یوصف کبره، و حکِی عن من حدثه من أهل المراکب الذین کسرهم البحر أنهم اضطروا الی المشی من نواحی فنصور الی لامری، و کانوا لا یمشون باللیل خوفًا من الزرافه لأنها لا تظهر بالنهار، فاذا أقبل اللیل صعدوا علی شجره عظیمه خوفًا منها، فاذا کان اللیل أحسّوا بها تدور حولهم، و یرون بالنهار آثار وطیها علی الرمل. و ان بالجزیره من النمل ما لا یوصف کثره، و خاصه بجزیره لامری، فان النمل فیها عظیم.

The text can be approximately parsed into: The same man told me that on the island of Lamri there are zarāfahs of such immense size that their magnitude cannot be described. It was reported by the shipwrecked sailors who spoke to him that they were forced to walk from the region of Fansur فنصور to Lamri. They would not walk at night out of fear of the zarāfah, because these creatures do not appear during the day. So when night approached, they would climb a large tree out of fear. Once night fell, they could feel the creatures circling around them, and in the daylight, they would see the traces of their footsteps in the sand. Also, on the island, there is an indescribably vast number of ants where the ants are enormous, and this is especially true on the Island of Lamri.

Unfortunately, Tai (2021) chose to equate zarāfah with giraffe. Based on the English translation published by Freeman-Grenville (1981), he produced the following translation

. . . 在蘭無里島上有非常高的長頸鹿。據說一些沉船的水手被迫從 Fansur 走到蘭無里,他們不敢在晚上行軍,因為害怕長頸鹿,而長頸鹿只在晚上出沒 . . .

And he was even able to justify and reinforce his misinterpretation by quoting references to qilin 麒麟 in Chinese literature and pairing qilins with some imaginary Acehnese giraffes.

- Captain ibn Shahriyar titled his collection: The book of the wonders of India: Its mainland, its sea, and its islands or Kitab Aja'ib al-Hind Barrihi wa Bahrihi wa Jaza'irihi كتاب عجائب الهند بره وبحره وجزائره.

The French translation of the Lamri zarāfah story, provided by P. A. van der Lith (b. 1844, d. 1901), is as follows:

Le même m’a appris que, dans l’île de Lâmeri, il y a des zarâfa (sarabha), d’une grandeur indescriptible. On rapporte que des naufragés, forcés d’aller des parages de Fansour vers Lâmeri, s’abstenaient de marcher la nuit par crainte des zarâfa. Car ces bêtes ne se montrent pas le jour. A l’approche de la nuit, ils se réfugiaient sur un grand arbre; et, la nuit venue, ils les entendaient rôder autour d’eux; et le jour, ils reconnaissaient les traces de leur passage sur le sable. Il y a aussi dans ces îles une multitude effroyable de fourmis, particulièrement dans l’île de Lâmeri où elles sont énormes.

Kruk (2008) cited the French translation and pointed out that zarāfah is a transcription of śarabha (शरभ). In Sanskrit, śarabha could be a reference to- some type of deer or antelope

- a powerful octopedal and mythical beast, stronger than a lion or an elephant.

Zarāfah زرافة is spelt with one explicit [a] and two implicit [a]: ZA-RA-FA-H. Although the modern zarāfah is usually tied to giraffe, the African ruminant quadraped with panther-like spots is unable to match the description given in the Persian account (e.g. it had a menacing appearance to the sailors and was nocturnal in nature). The only native animal in Sumatra that matches Ibn Shahiriyar’s description is the Sumatran rhinoceros. Primarily nocturnal, it feeds before dawn and after dusk, spending the daytime resting in muddy wallows to stay cool. The fact that zarāfah must be a reference to Sumatra was first realized by van der Lith (1883) when he first handled the Persian text, and it has since been repeatedly stressed by other authors such as Tibbetts (1979) and McKinnon (1988).

In Malay, the word is orthographically identical to its Arabic counterpart, yet pronounced girafah. This pronunciation suggests that the term likely entered the Malay world not through Arabic, but via a Romance language such as Latin, probably through Portuguese (girafa). The word made its way into the English lexicon in 1594 through Thomas Blundeville, who wrote: This beast is called of the Arabians, Gyraffa. See Mr. Blundevile: His Exercises Containing Eight Treatises Volume V, 7th ed., p. 551.

R. Kruk (2008) Zarafa: Encounters with the giraffe, from Paris to the medieval Islamic world, in B. Gruendler, M. Cooperson (2008) Classical Arabic humanities in their own terms: Festschrift for Wolfhart Heinrichs on his 65th birthday presented by his students and colleagues, Brill, Leiden, pp. 568 - 592. Buzurg ibn Shahriyar al-Ramhurmuzi (fl. 10th century) (1883-6), ‘Ajā'ib al-Hind. Livre des merveilles de l'Inde par le capitaine Bozorg fils de Chahriyar de Ramhormoz, ed. P. A. van der Lith and trans. L. Marcel Devic, Leiden. See p. 125 E. E. McKinnon (1988) Beyond Serandib: A note on Lambri at the Northern tip of Aceh, Indonesia 46, pp. 102 - 121.

- Dr. Tai remarked curiously: 有一點很奇怪的就是,我在中國的文獻也看見過有關亞齊有長頸鹿的記載。那就是說,亞齊的確有一段時間是有長頸鹿的。長頸鹿是非洲的動物,可以想像,他們其實連非洲都去過了 (One rather strange thing is that I’ve also seen records in Chinese sources mentioning that Aceh had giraffes. That would mean Aceh really did have giraffes for a period of time. Since giraffes are African animals, one can imagine that they had even traveled as far as Africa).

For example, see 王暉 (2008) 麒麟原型與中國古代犀牛活動南移考, 中國歷史地理論叢 23(2), pp. 12 - 22. In earlier Chinese texts, the qilin 麒麟 is identified as a rhinoceros and not a giraffe.

- A alternative Chinese translation of ibn Shahriyar's Persian text is as follows: . . . 他告訴我,在蘭無里島上,有一種名為扎拉法的動物,其體形之大,實難以言喻。有人轉述,一些船隻為海浪所毀的水手,被迫自班卒一帶徒步前往蘭無里。他們不敢在夜間行走,因畏懼扎拉法,此獸晝伏夜出。每當夜幕低垂,水手們便攀上一棵大樹以避其害。入夜後,常覺其獸在四周徘徊;及至白日,則於沙地上見其踐踏之痕。此外,島上亦有為數甚多之螞蟻,尤以蘭無里島為甚,其蚁之巨,駭人聽聞。

- The phrase min nawahi Fansur ila Lamri من نواحي فنصور إلى لامري is approximately: from the region of Fansur to Lamri, and it is correctly translated by G. S. P. Freeman-Grenville into ‘ . . . the Fansur coast towards Lamri . . ' But Tai again misinterpreted the region of Fansur as simply Fansur. Tai (2021) is of the opinion that Panchur in Wang (1350) cannot be the Fansur located on the northwest coast of Sumatra. It is evident that the Fansur coast refers to the larger Fansur region or the coastline of northwest Sumatra. However, Tai interpreted the extent of the journey as the distance traveled between two narrowly defined locales, and the distance between Barus and Lamri is more than 700 km, a distance that would be nearly impossible to traverse on foot.

Comments