Kok Kang Keow's petition to Cecil Clementi Smith (1885)

Petitioner, the widow Kok Kang Keow1, respectfully submits this petition.

Although my husband’s grave has yet to dry, the family fortune has already started to slip away. I earnestly beseech your grace to look kindly and with compassion upon the plight of a widow and her children. It is known that my late husband, Yap Tet Loy, was once entrusted with the post of Captain China, though it was merely empty name propagated vainly, with little actual asset.

Tracing back to the time when petty villians began to manufacture unrest and the region was left devastated in the flames of war and destruction, my husband diligently raised military provisions and distinguished himself repeatedly in battle. It is impossible to calculate the many efforts and resources he expended before gaining any benefit at all. The land he acquired was narrow and overgrown with wild vegetation. He had to reopen the settlement: cutting grass, building roads, repairing streets. He provided medicine and food to the sick, and coffins and burials for the deceased. But then natural disasters broke out. Year after year, the town suffered first a great fire, and then a flood. Shops and buildings collapsed and had to be rebuilt. Expenses from one task remained unfinished, and new demands for funds arose from another. The expenditure involved is truly beyond reckoning. Even any income or remaining goods he managed to obtain were mostly spent on these tasks. Furthermore, there remains an outstanding debt of over 150,000 dollars to Kwong Hang2, which has yet to be repaid.

Having just lost my husband, I am left with young children3 who cry out in hunger, waiting for food. Though we receive our daily rations, they still require continuous provision. The only hope for survival and repaying debts lies in the few remaining family assets left behind by my husband.

As for the market square4, it was originally part of a row of shop lots. During the time of the administration of Tuan Douglas5, small traders were ordered to be concentrated in one locale. So the shop lots were dismantled and the area rebuilt as the market square. Later, when Tuan Swettenham5 succeeded him, he ordered further demolition and rebuilding using bricks. All this was done in compliance with official orders. Yet due to this, the ground had to be cleared again and reconstruction started anew.

At that time, much planning and repeated effort was needed to achieve what little stands today. Indeed, when my husband first settled in the port of Kuala Lumpur, he achieved military merit and opened land for development. Thereafter, he worked tirelessly to attract trade and people to settle. All the towkays and traders in the port stood on ground he helped establish and remembered his kindness. In joint decision, they agreed to grant one dollar per bahara as a contribution — this was seen as a reward for his prior service, a humble token of gratitude, not an excessive demand.

Later, when Tuan Douglas was in office, he further changed the arrangement to pay 400 dollars6 per month as compensation for prior services. Clearly, this was not a regular salary but a distinct and special payment. Unexpectedly, the Selangor government7 then arbitrarily and promptly reduced8 the pension and sought to take back the market square under the pretext of jurisdiction. Alas! A debt of 150,000 dollars remains unsettled. My eldest son, Hon Chin (15.29), is still a young adult and he has no one to lean on. With debts pressing and daily expenses urgent, I truly have no means to escape nor magic to resolve the crisis. What can I depend on and not tremble with fear?

I reflect upon King Wen of Zhou, who ruled with compassion and was moved by the plight of the solitary. Even righteous martyrs were remembered and supported; how much more should widows be cared for? Compelled by desperation, I lay bare my sorrow in this appeal, hoping to receive grace and mercy from above.

I earnestly beg that the market square and the taxation scheme be returned to me in full. Once the Kwong Hang debt is fully repaid and Hon Chin is fully independent, I shall surrender the property as required.

I humbly implore your great benevolence to grant a space of convenience and extend pity to one suffering in deep hardship, to ensure that under Heaven, there is yet more Heaven. If this plea is granted, your petitioner shall never forget such life-saving kindness and grace as vast as the sky and earth.

With deepest gratitude and earnest submission.

Before His Excellency Tuan Rodger5, I humbly request that this petition be forwarded in full detail to His Excellency, the Governor of the Strait Settlements, and respectfully beg for its execution.

1 June 1885 (19th day of the 4th lunar month, 11th year of the Reign of Emperor Guangxu). Submitted respectfully by the widow, Kok Kang Keow.

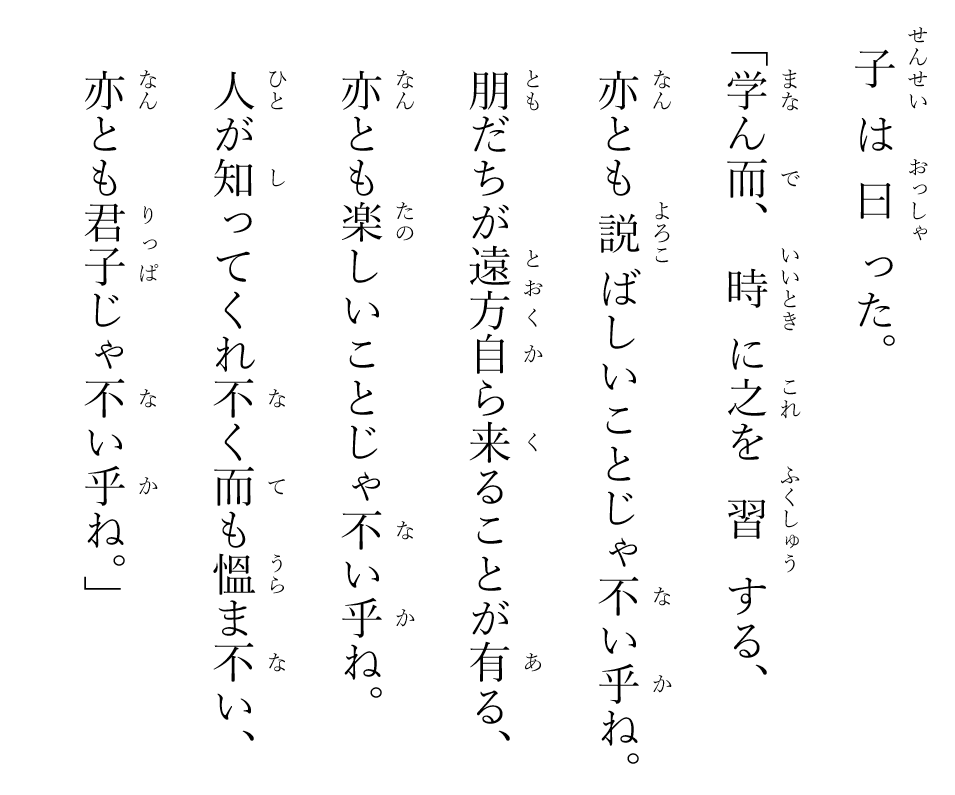

具禀人未亡人葉郭氏1,禀為夫土未乾,故業隨失,仰懇夫恩,俯憐孤寡事。窃以先夫葉德來蒙蒞以甲必丹之任,不過徒傳虛名,實無多業。

溯自小醜跳樑、時兵燹之餘,地方幾無遺類。從多籌軍餉,屢著戰功,不知幾費經營,然後始能得謐。 但土地窄狹,草木樷雜,復行開埧斬草、築路修街;為疾者施藥給粮,殁故者偹棺收殮。會天災流行,連年以來,既遭火災,又逢水患;街場鋪戶倒塌重建,此費未完,彼支又討。 此中動費,實不知凡幾;即曩者所獲,餘貨多從此處支銷。況尚欠廣恒2店貨項十五萬有奇,未經未欵。

現值未亡人母寡子幼3,待食嗷嗷,日逐口粮猶要供給,則先夫所遺下故業,全靠以此以作還賬之項、以為糊口之需。

其北索4之所,初時原是鋪戶一帶,緣前緞加叻5大王蒞時,欲小販買賣聚歸一處,即着拆卸,建為北索。迨緞唶喃5大王接任後,又着概行拆去,改建瓦磚,均皆遵命次舉行,是以又平地倒塌,重新葢造。當此之際,幾經綢繆,幾番動作,始能若是。然先夫於吉壠埔一埠,始則屢立戰功,廣開地利;繼而竭力維持,招商屯集,闔埠頭家、吧咧人等,莫不踐土懷恩,公同酌奪,每錫一扒抽銀一員,謂非報鴻恩,聊申蟻悃等語。而緞加叻大王在任時,又改作每月回酧兵先銀四百員6,是則兵先之酧,非比粮銀之項,明矣。不意吉壠埠公班衙7,將此兵先即行減8,卻又要此北索其握掌云云。嗟嗟!十五萬之欵未清,六尺之孤之依無所託,際此債項交迫,動費宜需,真是避債無臺,點金無術,其將何恃而不恐乎?

窃思文王發政,哀此煢獨;為先義士激揚,猶以孤寡為恤。迫得瀝情上訴,勢著望光哀鳴。仰懇天恩鴻施逾格,懇將北索之所、兵先之貲一併賜回,俟廣恒之數清還,兒子之俟廣恒之數清還,兒子之年及弱冠,才將北索即行奉上?�����將北索即行奉上。

伏望大發仁慈之心,早畱方便之地,垂憫苦中之更苦,務求天外之有天,俯俞允諾,則未亡人不勝深感再造之恩、覆載之德矣,沾恩切赴。

緞啰㘃5大王臺前,請轉詳三省大王御前,伏乞施行。

大英一千八百八十五年六月一号・大清光緒十一年四月十九日・未亡婦人葉郭氏謹禀。

- Kok Kang Keow 郭庚嬌 (b. 8 October 1850, d. 12 July 1924) referred to herself using the bisurname Yap-Kok 葉郭氏, literally, Kok in the Yap family. Although Frank Swettenham was nominally the Resident of Selangor when Yap Ah Loy died in 1885, he did not handle Kok's petition. When Hugh Low's one year leave (started in March 1884) was approved by Weld, Swettenham was transferred to assume the position of acting Resident of Perak, and J. P. Rodger was transferred to Kuala Lumpur to fill the vacuum left by Swettenham. Rodger continued to act for Swettenham until he was reassigned to Pahang, in 1889.

Sir Cecil Clementi Smith (b. 1840, d. 1916), the acting governor who rejected the Nyonya Bujang's petition.

Incidentally, Weld himself was also out of office (March 1884 to November 1885) and the power vacuum was filled by Cecil Clementi Smith, who showed zero empathy in the Nyonya Bujang's petition by saying that ‘he has received and considered her petition with respect to the market at Kuala Lumpur, and that he regrets that he is unable to entertain her prayer.'

- The owner of 廣恒 Kwong Hang is likely Yap Ah Shak.

- The widow was not exaggerating, her children were indeed all very young: Hon Chin 韓進 (15.29), Loong Shin 隆盛 (10.03), Leong Soon 隆顺 (5.11), Lóngfā 隆發 (2.68). For example, see the verse from Luo Binwang 骆宾王 (b. 640?, d. 684?): 一抔之土未干,六尺之孤何托?The soil on the late emperor’s grave is not yet dry, yet our young lord does not know whom to rely on! 六尺 (6 chi) is a reference to the height of a young adult, since the height of Confucius is 9.6 chi, 6 chi is approximately 62.5% of a full grown adult. The exact length of chi in Zhou dynasty cannot be conclusively determined but it is reasonable to suppose that \(尺 \in (18.18, 23.03)\) mm, thus the numerical bracket for 6 chi is 110 mm to 140 mm.

The widow could never have imagined that one day, thirteen years later, she would be sued by these very children once they had grown taller.

- The Nyonya Bujang called the market square (present-day Old Market Square) 北索 (baksaak). It is the phonetic approximation of pasad or pasar (Another transcription found in Victorian Malaya is 口 × (巴 + 虱) = 吧虱). Pasar فاسر is a Persian loanword بازار (bazar = market place). The exact reason why the last consonant was corrupted (فاسد) from r to d when the word was transliterated into the Chinese is not known.

Present-day Central Market is not the baksaak referenced by the widow in the letter. Central market (buildng cost = $42,780, land cost = $5,000) emerged as a compromise to relocate traders from the Old Market Square, enabling them to operate in a more hygienic and organized environment (see Barlow (1995), p. 250). In 1883, Yap Ah Loy grew agitated when Swettenham revealed his intention to repurpose ‘his' Old Market Square for more efficient commercial use.

- Tuan Douglas 緞加叻 and Tuan Swettenham 緞唶喃 are references to the second and third Resident of Selangor. Tuan Rodger 緞啰㘃 was a reference to J. P. Rodger, who acted on behalf of Swettenham when he was away in Perak.

- On 31 December 1877, at the fourth Council meeting of Selangor, Yap Ah Loy's allowance was initially fixed to 200 dollars. However, in February 1879, Yap Ah Loy's stipend was increased from 200 to 400 dollars, with the adjustment applied retroactively from January 1878 (1957/0000861W). This pension 兵先 was established by Bloomfield Douglas (and approved by Sultan Abd al-Samad) as compensation for the removal of his traditional right to levy a tax on tin transported through Klang—previously fixed at one dollar per bahara. This privilege was terminated on January 1878. Following Yap Ah Loy’s death, his widow, Kok, received a pension of 200 dollars per month until her death (1957/0231678W).

Two years after the Klang Civil War was brought to an end, Yap Ah Loy sought to double the tax rate from one to two dollars per bahara. However, his proposal was blocked by Resident Bloomfield Douglas after tin merchants lodged formal complaints.

Actually, in 1875, Yap Ah Loy attempted to revise this tax rate from one to two dollars per bahara. However, the proposal proved unpopular among the tin miners and contributed to a labor exodus from the town. In August 1875, Douglas intervened by writing to Yap, requesting that he suspend the implementation of the new rate and revert back to old rate of one dollar per bahara (1957/0000061W). Similarly, Dato' Dagang's tax-levying previlege (also at a rate of one dollar per bahara) was commnuted for a pension in 1877. In 1885, one bahara of tin was approximately 91 dollars. In 1872, Kuala Lumpur was producing 1,000 bahara per month, in 1889, the amount rose to 182,236 pikuls per year or 5,062 bahara per month (see Sadka (1968), pp. 14, 21, 309).

Tin-derived tax revenue generated by Selangor (Annual Report, Federated Malay States, 1896, Special General Return) is as follows:

Year Tin

duty

(dollar)Average

monthly

tin output

(bahara)1872 - 1,000 1873 - 1874 - 1875 - 1876 - 1877 - 1878 111,920 755 1879 107,558 725 1880 100,586 678 1881 126,038 850 1882 161,832 1,091 1883 180,002 1,214 1885 225,254 1,519 1886 302,530 2,040 1887 450,365 3,037 1888 526,742 3,552 1889 750,634 5,062 1890 672,667 4,536 1891 672,633 4,536 1892 828,326 5,586 1893 1,082,004 7,297 1894 1,402,174 9,456 1895 1,520,927 10,257 1896 1,377,325 9,288

- 公班衙 Gōngbānyú is the Chinese transliteration of the Dutch word ‘compagnie'. For example, in a letter written by an officer in Qianlong's administration (4 February 1795), VOC (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie) is known as 荷蘭公班衙. In this letter, 公班衙 is simply a reference to the colonial government headed by the Resident.

- In his 1879 letter to Sultan Abdul Samad (1957/0000861W), Yap Ah Loy expressed his gratitude and acceptance of the monthly allowance of 400 dollars, declaring it a full and final settlement of any claims he might have had against the Selangor Government. In return, he solemnly pledged his loyalty to the Sultan and the state.

This formal and conciliatory tone stands in stark contrast to the words of his widow years later, who lamented:

. . . 又改作每月回酧兵先銀四百員,是則兵先之酧,非比糧銀之項,明矣 = . . . the pension of 400 dollars, though termed a reward for past service, is clearly not comparable to the fund needed to sustain our daily provisions . . .

Her statement reframes the allowance not as an honorific gesture but as inadequate for basic survival, highlighting the widow’s financial distress and the shift in perception from loyal gratitude to desperate appeal. Actually, Yap Ah Shak only received 100 dollars as his monthly allowance and the amount was revised to 200 dollars when Yap Kwan Seng took over the role, and the amount was only adjusted five years later to 225 dollars in 1895. It is likely that Kok was aware of the allowance for the successor of his husband was slashed from 400 dollars to 100 dollars, which may explain why she used the phrase: . . . 不意吉壠埠公班衙將此兵先即行減,卻又要此北索其握掌云云 . . . = . . . it was unexpected that the Selangor government promptly reduced the pension, and yet still demanded control over the market place . . .

Comments