Yap-Douglas letter (1877)

Water disruption at Pangkalan Lumpur

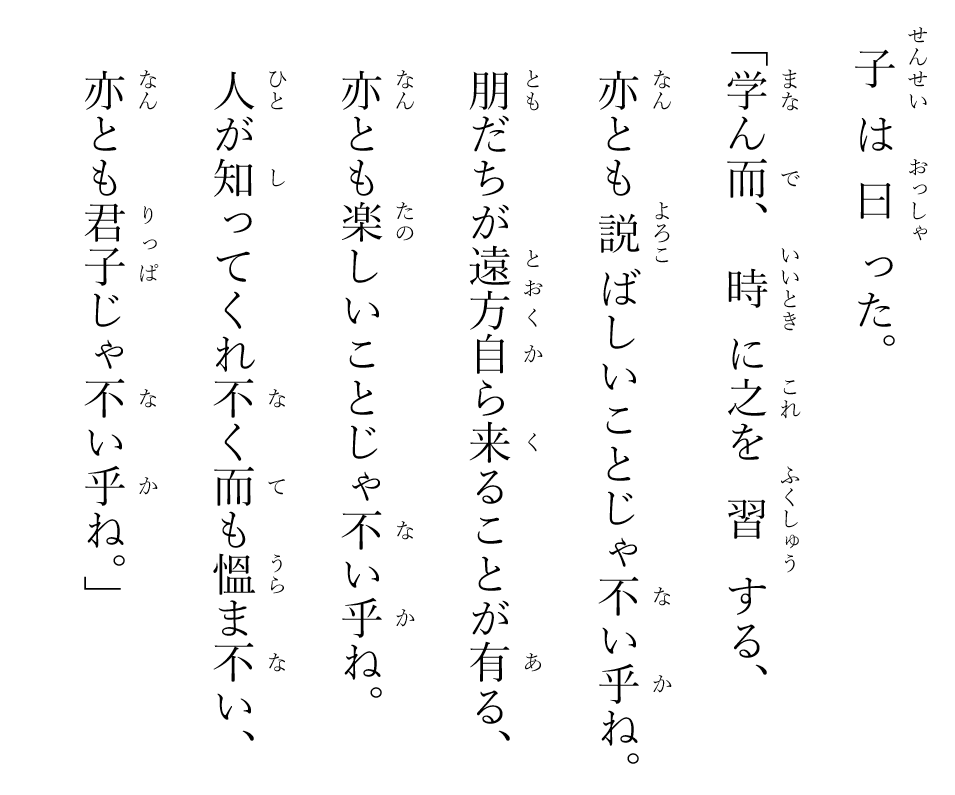

On 29 March 1877, Yap Tet Loy 葉德來 wrote a letter to Bloomfield Douglas to relay a water-related grievance at Pangkalan Lumpur tin mine. This letter is important because it contains several important metadata:

- An Indic title was invoked by Yap Ah Loy and he called himself Kaptan Klang dalam Kuala Lumpur.

This wooden stamp (shown in mirrored form) can be found in the Sin Sze Si Ya Temple Pioneers of Kuala Lumpur Museum 吉隆坡師爺廟拓荒博物館. This stamp is likely a replacement copy built later since its impression does not perfectly conform to the Chinese characters found in the letter dated 29 March 1877.

- In the stamp, the Captain styled his residence/office as Tet Sang of Klang 吉隆德生.

- The two place names, Kuala Lumpur کوال لمفر and Pangkalan Lumpur فڠکالن لمفر are seen together in the same document. The Captain's usage appears to show that Pangkalan Lumpur was a point reference, and Kuala Lumpur was an areal reference to the area containing Pangkalan Lumpur, centered at the Market Place confluence. In other words, Pangkalan Lumpur is a subset of Kuala Lumpur.

- See 1957/0000387W. Douglas was the Resident of Selangor from April 1876 to August 1882.

- In Devanagari script, Sri Indra Perkasa Vijaya Bakti is श्री इन्द्र प्रकाश विजय भक्ति (Śrī Iṇḍra Prakāśa Vijaya Bhaktī) or শ্রী ইন্দ্র প্রকাশ বিজয় ভক্তি in Bengali script. This shows that back in 150 years ago, it was perfectly reasonable for Malay courts to install their subjects with Indic titles and decorations, similar to the practices recounted in Sejarah Melayu. However, the way Yap addressed himself was not consistent, for instance, in 1881, he called himself Kaptan Cina Kuala Lumpur and not Kaptan Klang dalam Kuala Lumpur کفتن کلڠ دلم کوال لمفر but he used his Indic title consistently. See Arkib Negara Document Number 1957/0001366W.

- Lubis (2018), in p. 533, listed several examples (in Middlebrook's papers) in which the names Pangkalan Lumpur and Kuala Lumpur were mentioned in isolation.

Pangkalan Lumpur (1) Letter from Tunku Kudin to Yap Ah Loy (dated 15 November 1873): . . . kepada Kaptan Yab A-loy yang ada pada masa ini di dalam Pangkalan Lumpur adanya . . . (2) Letter from the Sultan to Yap Ah Loy (dated 10 April 1875): . . . menyatakan kepada Kaptan Cina di Pangkalan Lumpur . .

Kuala Lumpur (1) Letter from the Sultan to Yap Ah Loy (dated 9 November 1874): . . . kehadapan paduka sahabat kita Sri Indra Perkasa Vijaya Bakti, Yab A-loy, Kaptan Cina, Kuala Lumpur dengan beberapa selamatnya . . .

- Pangkalan فڠکالن is a derivative of pangkal (terminal point in Malay). One effect of adding the an-suffix to a Malay word m is the production of m-an, which is a noun representing an object/place closely associated with m. ‘Pangkal + an' is normally invoked in land/sea travel to mean disembarkation point, e.g. Pangkalan Batu.

Another example is empang + an = empangan (the end result when a river is dammed). Empang امفڠ (barrier/blockade) was borrowed to denote tin mine. Technically, empang describes only a subfeature of tin mine, i.e. the body of still water resulted from paydirt excavation.

Apparently, present-day Ampang is derived from ‘empang'. Other examples: Ampangan (the official residence of the Undang of Sungai Ujong), Ampang Tinggi in Kuala Pilah (the official residence of Tunku Besar Seri Menanti), Kampung Ampang Batu in Seri Menanti, Jalan Ampang in Tambun, Perak. These toponyms are all physically and historically tied to tin mines.

Kuala کوال in Malay simply means a junction point in water transit networks. In the binary case (\(n = 2\)), any two elements in a network can meet to form a kuala (e.g. river-sea, river-lake, etc). For \(n = 3\), we have the typical river-river-river triple point.

Yap's lamentation shows that Pangkalan Lumpur must be either (a) the actual mining site or (b) very near the actual mining site.water. This is what we inform our friend. Written on 14 Rabi al-Awal 1294 (Thursday, 29 March 1877, 丁丑年2月15日). The letter was stamped and sealed with the following word in red ink: Jílóng Déshēng shūjiǎn 吉隆德生書柬. Jílóng 吉隆 is a reference to Klang or Klang Valley during Yap's era. Déshēng 德生 (Tet Sang) is the name of Yap's office (Tet Sang Apothecary 德生堂 was likely co-owned by Yap Tet Sang 葉德生 and the Captain China). shūjiǎn 書柬 can mean ‘letter from/letter written by'. The romanized Malay text is given as follows:

Surat tulus dan ikhlas daripada beta

Sri Indra Perkasa Vijaya Bakti

Yab Loy Kaptan Klang di dalam Kuala Lumpur

Apalah kira ke hadapan majlis sahabat beta

Tuan Bloomfield Douglas, Royal Naval ResserveyRNR

Yang menjadi Berhormat Residen Selangor

di dalam Pangkalan Batu adanya

Opas daripada itu

beta permaklum maka kepada sahabat beta

oleh seperti surat Sultan Abdul Samad yang diantar

kepada beta itu sampailah dengan selamatnya

Pahamlah yang tersebut di dalamnya

dan lagi adalah suwatu fasal, utang kepada

Tuan Guthrie itu

beta sudah suruh orang turun pergi ambil

timah Selangor di dalam dua tiga empat hari ini

Barangkali sampailahnya

Dan suwatu, beta di dalam Pangkalan Lumpur

banyak susah karana air tiada hendak lancur

Maka inilah beta permaklumkan

kepada sahabat beta adanya

Tertulis kepada 14 haribulan Rabi' al-Awal 1294

سورة تولس دان اخلاص دارفاد بيت

سري اندرا فرکاس وجاي بقتي

يب لوي کفتن کلڠ د دلم کولا لمفور

افاله کير کهادفن مجليس صحابة بيت

توان بلومفيلد دوکاس ار ان ار

يڠ منجادي برحرمت رسيدن سلاڠور

د دلم فڠکالن لمفر ادڽ

اوفاس دارفد ايت

بت فرمعلوم مک کفد صحابة بيت

اوله سفرت سورة سلطان عبدالصمد يڠ دانتر

کفد بيت اتو سمفيله دڠن سلامتڽ

فهمله يڠترسبت د دلمڽ

دان لاگي ادله سواتو فصل اوتڠ کفد

توان کتري ايت

بيت سوداه سوروه اورڠ تورون فرگي امبل

تمه سلاڠور د دلم دوا تيگ امفت هاري اين

برڠکاي سمفيله ڽ

دان سوات بيت د دلم فڠکان لمفور

باڽق سوسه کارانا اير تيادا هنداق لنچور

مک انله بيت فرمعلومکن

کفد صحابت بيت ادڽ

ترتولس کفد 14 هاريبولن ربيع الاول 1294

Daripada is a composite word built from dari در and pada فد. The word appears twice in the letter: (a) Daripada beta = from me. In Hindi, beta बेटा means son. In this context, the word functions as a humble euphemism for self, deliberately signaling a lower position within the social hierarchy relative to the addressee, not unlikely 在下 or 僕 in classical Chinese (e.g. father v. son, up v. down, master v. servant). For example, in a letter written between 11 March 1480 and 9 April 1480, the 6-year-old Sultan Mahmud metaphorically addressed Shō En 尚円 as his father . . . 伏望琉球父王多蒙欽賜敕書封賞 . . . The feminine form of beta is beti बेटी, e.g. beti-beti perwara (court damsels). Wilkinson tells that the Malay kings on the east coast use kita to refer to themselves, while their counterparts on the west coast use beta. Wilkinson's observation is always correct. For example, both Tunku Kudin and Sultan Abdul Samad employ kita کيت in their letters to Yap Ah Loy (b) Opas daripada itu = Messenger from (the Residency at Pangkalan Batu), opas is a Dutch loanword, from opasser. Pada is a Sanskrit loanword meaning feet and it is cognate with the Latin word ped. When it is used as a noun, it is spelt فاد, however, it is spelt with the aleph omitted (فد) when it is used as preposition (at, from, to). In Yap's letter, both dari and pada were spelt with an extra aleph. Apalah kiranya is equivalent to: (a) if it would be possible . . . (b) Would it be too much to ask . . . (c) Might I humbly ask . . . (d) Would you kindly . . . The word kira shapes the probabilistic tone. The Chinese equivalent of ke hadapan majlis is 䑓前.

Surat Yap Ah Loy kpd Residen Selangor, 1877.Antara kandungannya Yap Ah Loy mengadu di Kuala Lumpur tak ada air hingga tak boleh mengepam air di lombong."Dan suatu beta di dalam Pengkalan Lumpur banyak susah karena air tiada hendak lancur".https://t.co/dYjaBFgedZ pic.twitter.com/JG4qReZaOi

— Saufy Jauhary 🇲🇾🐦 (@SaufyJauhary) October 12, 2021

Transition from Cold 冷 to Prosperous 隆

In one of Yap's earlier seal, the word Klang is transliterated as 吉冷. Since 冷 (laŋ¹, meaning cold) is phonetically a more correct glyph to transcribe the /laŋ/-phonem in k

After helping Yap to win the Kuala Lumpur battle, the former was given the title Orang Kaya Imam Perang Indra Gajah and the latter was named Orang Kaya Imama Indra Mahkota.Pahang army, regained control of Klang River from Raja Mahdi and Raja Asal in 24/25 February 1873, and he needed a quasi-similar and an auspiciously-sounding glyph.

隆 (luŋ², meaning prosperous) seems to be a perfect candidate. This explanation can be applied to illuminate the Yap Hon Chin 葉韓進 passed away on 5 January 1933 (Thursday) but his death was reported only 4 days later. This was in stark constrast with the treatment given to his mother by the press and the colonial officers in 1924.

Within a \(\frac{1}{4}\)-century after his father died, Yap Hon Chin was both a bankruptee and banishee (see the letter from the Kuala Lumpur Superintendent of Prisons to the secretary of Selangor Resident, dated 4 August 1909, 1957/0148800W).

Yap's second son, Yap Loong Shin 葉隆盛, was born on 4 April 1875 and was mothered by his second wife named Kok Kang Keow 郭庚嬌 (1849? - 12 July 1924), a Nyonya from Melaka, whom Yap married in 1865, three years after he settled in Kuala Lumpur.

The second output from Kok was 葉隆顺, died when he was only 27.8 years ago (b. 6 March 1880, d. 8 December 1907).

Another half-brother of Hon Chin was 葉隆發 (b. 10 August 1882, d. 21 September 1900). He was mothered by another concubine of Yap Ah Loy named He 何氏, and he died young like another half-brother of his, when he was only 18.1 year-old. Probably because of this, his mum adopted another son named 葉隆森middle-name difference between his first son and his second son. When his second son was born in 1875, the boy was given the name 葉隆盛 (Yap Loong Shin), while his first son, 葉韓進 (Yap Hon Chin, born 1869 in Melaka), was given a different middle name.

(a) Selangor - (Sz-nga-ngok 師牙岳, Sut-lang-ngo 雪蘭鹅, Kit-lang 吉冷) and most commonly residents outside the state call Kit-lang (Klang), p. 193.

(b) Kuala Lumpur - (Kat-lung-po 吉隆坡) and Firmstone added that he also often heard kai-(or ka-) lam-po, p. 192.

(c) Kuala Selangor - (Sek-a-ngo kang-khau 昔仔午港口) and remarked that these are Hokkien souds, representing the mouth of the Selangor River, p. 192.

(d) Klang - (Pa-sang 吧生) - and he claimed that the name was given by the Malays to the town of Klang, p. 191. H. W. Firmstone's remarks on Kit-lang supports our postulate that the place name was first known to Yap (while he was still in Lukut) as 吉冷 and when he repeated the the same transcription in his seal when he settled in Kuala Lumpur. This seal was found together with a personal seal of Cheow Ah Yok 趙煜榮. It is likely that both seals were kept by Chew Yee Yoke 趙如玉, Yap's daughter-in-law and Cheow's daughter. The seals were offered (probably by Chew Yee Yoke's children) to an antique store in the 1970s but their current location is not known.

Captain Yap's birth/death can be compactly expressed in their sexagesimal forms: 丁酉癸卯丙辰庚寅 and 乙酉庚辰庚子己卯.calendrical data (5 am < 卯時 < 7 am) written on the photo: 終於光緒十一年乙酉歲三月初一卯時・一八八五年四月十五卯時 (died on the 11th Year of Guangxu, 1st Day of the 3rd Month of the Year of Yiyou - 15 April 1885 - Hour of the Rabbit). We were told by the same newspaper clip that Captain Yap was honored with two series of five-gun salute (10 o'clock, fired from the Joss House = Sin Sze Si Ya Temple 仙四師爺廟???Joss House, and 7 o'clock the next morning when the body was placed in the coffin.

Sungai Lumpur in Irving's Map (1872)

If the aforementioned treatment is correct, we posit that 隆坡 is etymologically unrelated to the Malay word ‘lumpur لمفر'. This theory is not really new because Hsu Yun Tsiao 許雲樵 surfaced the same idea back in 1961.

Lam-pa 濫吧 = wet ground; a marsh.

Khui-pa 開吧 = to bring such ground under cultivation.

Khoe-pa 溪吧 = a river bed.

Note that the word Lam 濫 can mean both flood and disorderly. For instance, 濫使食 lām-sú tsia̍h (eat indiscriminately).Lampa),Lumpur就是濫巴的譯音,所以在馬來文字典內是Loompoor can be found in A Dictionary English and Malayo, Malayo and English. The dictionary was produced by Thomas Bowrey in 1701.找不到Lumpur這個字的。

When

However, the analysis given by Hsu in the Actually Hsu's opinion in the second part of the first paragraph (the relationship between 坡 and 埠) is also problematic.second paragraph are inappropriate and completely off-tangent, because lumpur is a legit Malay word and it is not a Chinese loanword. In R. J. Wilkinson's Malay-English dictionary (p. 610), we have:

لمفر lumpor. Mud, slime. Sa-ekor kĕrbau membawa lumpor, sĕmuwa kĕrbau terpalit: if one buffalo is covered with mud all the rest of the herd will be smeared with it; one scoundrel will corrupt the whole gathering; Proverbial expression, Hikayat Abdullah 24. Laut lumpor: a sea of mud; Hikayat Abdullah 357. Lumpor kĕtam: hard mud perforated with crab-holes, such as is often met with near high water-mark.

Note that in 1901 Wilkinson omitted both vowels in ‘lumpur' and rendered the word as

. . . Kuala Lumpur sebenarnya memiliki Sungai Lumpur sebelum ia ditukar nama kepada Sungai Gombak pada 1875 atas sebab yang tidak dapat dipastikan . . .

Now the question asked by Hsu in 1961 on why the triple point was not named ‘Kuala Gombak' could be partially solved if we take Khoo Kay Kim 邱繼金 (1937 - 2019) and his interpretation on Irving's map (1872) as the final word, that Sungai Gombak was simply known earlier as Naming substreams of river is tricky, e.g. we can also call left-branch with Simpang Kiri and the right-branch with Simpang Kanan (in Batu Pahat river for instance).Sungai Lumpur and the name was changed to Sungai Gombak around 1875.

But Khoo's remark is hardly authoritative in this matter.

A more plausible statement is that Anderson visited Klang/upper reach of Klang river in 1822 or 1823 or 1824, and most likely 1823 if you want me to bet, since his book was published in 1824.Lubis (2013) Sutan Puasa: the founder of Kuala Lumpur, Journal of Southeast Asian Architecture 12, pp. 24 - 37).

Mr. Anderson's Lumpoor (1824)

Now we digress to a paragraph written by See also J. Anderson (1824) Political and commercial considerations relative to the Malayan Peninsula, British settlements in the Straits of Malaya, William Cox.

See also Anderson's Malayan Peninsula (Description of the tin countries on the Western coast of the Peninsula of Malacca from the Island of Junk Ceylon to the River Lingi near Malacca and the Rivers on the Coast etc) in Singapore Chronicle and Commercial Register, 4 June 1836.John Anderson in 1824 about Klang (Colong):

. . . is about 200 yards wide at the mouth, but narrows to 100, and in some places 70 after a few reaches. The channel is safe and deep in most places, and th current very rapid. The first town is about 20 miles from the entrance, called Colong. It is situated on the right bank, and defended by several batteries. Here the King of Salengore resides at times. The inhabitants, before the war with the Siamese at Perak in 1822, were reckonded at about 1500, and the following are the names of the villages upon the river, as far as within one day's journey of Pahang, on the opposite side of the Peninsula, viz . . .

Teluk Gading

Sungei Dua

Teluk Puleh

Sungei Binjek

Pankalan Batu

Kampong Lima Pulu

Bukit Kechil

Puatan

Bukit Kruing

Bukit Kuda

Sungei Bassow

Naga Mangulu

Kampong Lalang

Bukit Bankong

Sungei Ayer Etam

Penaga

Petaling

Sirdang

Junjong

Pantei Rusa

Kuala Bulu

Gua Batu

Sungei Lumpoor

For the toponyms marked with red ink, an additional remark was appended by Anderson:

At all these places, tin is obtained, but most at Lumpoor, beyond which there are no houses. Pahang is one day's journey from Lumpoor.

If we take a step back and a deep breath to consider the fact that Irving's map and Anderson's remarks were gapped by approximately 50 years = Plenty of time for interpolations and corruptions50 years, and probably we should reset our analysis by giving more weights to Anderson's writing. Note that contemporaries of C. J. Irving such as F. Swettenham tried to resolve the same etymological puzzle but was unable to locate a convincing solution.

Placenames in maps may be easily revised and altered by cartographers and we have no easy way to extract the etymologically correct toponyms by just merely looking at them. For instances, we have the following revisions:

- Sungei Ulu Klang in Irving's map (1872) was left unmarked in de Souza's map (1879).

- Sungei Lumpoor in Irving's map was grown and bifurcated into Sungei Gombah and Sungei Batu in de Souza's map.

de Souza's choice of leaving the Sungai Ulu Klang branch unmarked was accompanied by two new markers: Kwala Lumpor (کوال لمفر) and a police station (P.S.). If we couple the modern fact that the the toponym Ampang is yet to be invented/marked in the de Souza's mapAmpang region is alluvially richer than the east bank of Klang River, and Anderson's comments that most tins can be obtained in Lumpoor and Pahang is Jalan Pahang is on the east bank of the Klang river, situated just next to Titiwangsa.one day from Lumpoor. One cannot help but to conclude that Anderson's Lumpoor is in fact the east bank of the Klang river or the Titiwangsa | Ampang | Kampung Dato Keramat is previously known as Kampung Tangga China.

J. C. Pasqual (1934), based on his Malay sources, tells us that: . . . Supplies for the mines were brought up by boats as far as the kuala of the Lumpur river near the new mosque and thence carried by coolies through the jungle to the mines. The Lumpur river joins the Klang River at Tangga China a mile upstream from the town of Kuala Lumpur (which consequently is a misnomer). . .Kampung Dato Keramat region.

If Anderson's Lumpoor is present-day Ampang, then Anderson's Sungei Lumpoor is likely the Ulu Klang fork of the Klang River.

Median 中央値 is pronounced chūōchi (チュウオウチ), which incidentally, is also how

Abdullah-Chee-Jumaat-Lim joint venture (1857)

When Raja Sulaiman bin Sultan Muhammad ibni Sultan Ibrahim died in 1853 is traditionally given as the year when Raja Abdullah was appointed as the Governor of Klang by Sultan Muhammad.

We need to revise the number from 1853 to 1850 in light of a copy of the appointment letter which says that Raja Abdullah appointed in 1266 AH (i.e. 17 November 1849 < 1266 < 5 November 1850). 1850, he was not succeeded by his son Raja Mahdi. Instead, Raja Mahdi's grandfather brought in Raja Abdullah bin Raja Ja‘far (d. 1869) to govern Klang. Within a few years, Raja Abdullah was able to step-change the productivity of tin in Selangor. Low productivity is evidently clear from the It is clear from Sultan Ibrahim's lamentation that the early miners in Anderson's Lumpoor were not aided by any hydraulic technologies, and they have zero ability to draw water to the mining sites. So they were only able to lancur with rain water.

It was very likely that the Abdullah-Jumaat joint venture, with the capital loaned from Chee and Lim, was able import the water-ladder pumps 龍骨水車 or chin-chia 轉車 from China and used them effectively in present day Ampang.

Water-ladder pump (actuated by the circular motion of limb muscles) is a staple piece of hydraulic technology to move water around paddy fields in Southern China. Eventually, leg-powered water pumps were replaced by steam-powered water pumps (introduced in 1881 by Yap) and diesel-powered water pumps.following remark by the old Sultan Ibrahim ibni Sultan Salehuddin Shah in 1818 is approximately 12 years after Raja Ja‘far departed from Selangor.

Raja Ja‘far, the father of Raja Abdullah, was the governor of Klang from 1804 - 1806. In 1806, he was summoned back to Riau by Mahmud III to take the position Yang diPertuan Muda of the Johor-Pahang-Riau-Lingga Kingdom.

Five years later, when Mahmud III died in Lingga, Raja Ja‘far installed Abdul Rahman as the new Sultan, which was the opening chapter of the end of the Johor-Pahang-Riau-Lingga empire.1818:

If there is rain, the miners can work, but if there is no rain, they cannot.

What was Raja Abdullah's recipe? In 1857, he partnered with his older brother, Sultan Muhammad appointed Raja Jummat as the governor of Lukut in 1846.Raja Jumaat bin Raja Ja‘far (d. 1864), and they took a loan of \(0.3 \times 10^5\) Spanish dollars from two Baba merchants in Melaka (Chee Yam Chuan 徐炎泉 b. 1819, d. 1862, and Lim Say Hoe 林西河). The Abdullah-Chee-Jumaat-Lim (ACJL) joint-venture was able to mobilize \(n\) Huizhou miners and \(m\) Mandailing miners (\(n = 87, m = ?\)) from Lukut and send them to present-day Ampang.

$$\underbrace{\textrm{pay dirt}}_{\textrm{1806 to 1857}} \xrightarrow[{\rm H_2O}\,{\rm (rain)}]{\rm lancur\,separation} \underbrace{\textrm{watery dirt}}_{\rm lumpur} + \underbrace{\rm SnO_2}_{\rm tin\,⥁}$$In a statement given to H. C. Ridges on 11 March 1904, approximately 4.4 years before he died, If Sutan Puasa was about 70 years old in 1904, then he was probably born in 1834. Sultan Abu Bakar of Johor was also born around the same time.

It means that Sutan Puasa was a young man of 25 years old when he migrated to Kuala Lumpur from Lukut around 1859. Liu Ngim Kong was also a young of 24 in 1859 since his son Low Koon Fatt claimed that his father was only 33 years old when he died in 1868.

. . . been in this country for40 years , was made headmen or tantamount to headmen, in Kuala Lumpur in the time of Sultan Muhammad, father of Raja Laut. My immediate chief, Raja Abdullah of Klang, appointed the first Captain Ah Siew (Ah Siu) a Hakka. I came from Lukut, and with me came bothAh Siew and oneLoh Chye . . .

If Sutan Puasa's last sentence is to be taken seriously, then the following must be true: the Huizhou-Mandailing trio: Sutan Puasa, Hew 邱秀, and Given the fact that Low's sons are named Low Koon Swee and Low Koon Fatt, his surname should rightfully be rendered as ‘Low' instead of the ‘Liu' (Huizhou rendering of 劉). Low is the Hokkien rendering of 劉. Remember that Low's family was based in Melaka and Melaka was dominated by the Hokkien dialect.

In a petition letter filed by Low Koon Fatt on 1 March 1904, his father's name was spelt Pah Loh Chye (with an additional ‘Pah' appended before Sutan Puasa's ‘Loh Chye' (likely a roman transcription of 劉仔. Pah is unlikely to be Low's surname, it is probably an affectionate Malay honorific of ‘Pah' or ‘Pak', which has the Chinese equivalent of 伯); In J. C. Pasqual (1934), Low's name was spelt Pak Loh Tsi); In a short biograph of Yap Ah Loy in the Straits Times (20 April 1885), his name is spelt Pah Lok Chai.

It was mentioned in the petition that his father was only about 33 years old when he died in 1868 (this indicates that Low was probably two years older than Yap Ah Loy). The name of Low's wife was mentioned as Wee Kiow Neo. We also know that the cremated remains of Low was left in Sin Sze Si Ya Temple.Low 劉壬光 reached But we know Hew and Low built their residences 三間莊 near the bifurcation point, to facilitate upload and download of goods.Ampang together in between 1857 and 1859 (most probably in 1859). Sweet-Potato-Sze or Yap Ah Sze 葉茨 was probably one of the early inhabitants but his name was not mentioned by Sutan Puasa.

We are pretty sure that the east bank of the Klang River or present-day Ampang region was already sparsed populated and they told Anderson that the name of the place was Lumpur, named semi-humorically by the inhabitants to describe the physical state of the land, induced by lancur separation during rainy seasons.

$$\underbrace{\textrm{pay dirt}}_{\textrm{after 1857}} \xrightarrow[{\rm H_2O}\,\textrm{(龍骨水車)}]{\rm lancur\,separation} \underbrace{\textrm{watery dirt}}_{\rm lumpur} + \underbrace{\rm SnO_2}_{\rm tin\,⮥}$$The contribution of the ACJL joint venture was that they re-injected hydrotechnology and reliable human labor to the east bank of Klang River. And Klang was upgraded to a tin export town as the result of the amplified output.

Tunku Kudin was the paternal uncle 五叔公 of Tunku Abd al-Rahman, the first Prime Minister of Malaysia.Ḍeya' al-Din of Kedah (1835 - 1909, تنکو ضياء الدين). Raja Nuṭfah was initially betrothed to Raja Mahdi bin Raja Sulaiman was the governor of Klang. Based on a appointment letter dated 1266 AH (17 November 1849 < 1266 < 5 November 1850), we have reasons to posit that Raja Abdullah bin Raja Ja‘far ( - 1869) took over his seat after he died in 1850.Raja Sulaiman bin Sultan Muhammad Shah (? - 1882), but her father Sultan Abd al-Samad (r. 1859 - 1898) cancelled the engagement because Raja Mahdi failed to keep up to his promise of giving a fix cut ($500 per month) from his Klang revenue to his would-be father-in-law. Raja Nuṭfah was eventually married to Tunku Kudin in June 1868 (unfortunately she did not get along very well with Tunku Kudin or the royal household of Kedah, she was escorted back to Kuala Langat in 8/9 August 1879 by Tunku Yusof, Tunku Kudin's younger brother, within less than a year after her father accepted the resignation letter of her husband on 31 October 1878 | 5 Zulkaedah 1295). J. H. M. Robson (in Selangor Government Gazette 1894, p. 540), described Tunku Maharum as ‘a very beautiful Malay princess'. Robson's comment was reasonable as she probably inherited Raja Nuṭfah's youthful good-looks. 1868 is a very important marker year in Selangor, because Princess Nurfah's husband was installed as the Viceroy of Selangor on 24 June 1868 (5 Rabi al-Awal 1285, Wednesday), and it disturbed the power structure in Klang Valley, which was then dominated by Raja Mahdi (r. March 1867 - March 1870). Two months after Tunku Kudin's appointment, the second Captain Klang 吉冷甲政, Low (劉壬光), died in the 7th lunar month of the Year of Wuchen 戊辰 (ca. between 18 August and 18 September 1868, \(2024 = 1868 + 60\times\frac{13}{5}\)). In June 1869, Yap was officially installed by Raja Mahdi as the successor to Captain Low. Yap was in an awkward position because he was not in a good position to accept or reject Raja Mahdi's gesture, given the fact Yap was aware of the cancellation of Mahdi-Nuṭfah union and the appointment of Nuṭfah's husband as the underking of Selangor, as these are indications that Raja Mahdi would soon be ousted from the Klang power sphere..

Comments