Sundaland in the Malay World

Kami Dayak, kami bukan Melayu. Dayak dan Melayu adalah dari ras Austronesia. Tidak perlu memelayukan bangsa-bangsa yang bukan Melayu ok.

Comment by a viewer named @borneandayak6725 on the clip titled:

Asal Usul Melayu, Induknya Di Benua Sunda

MISINTERPRETING WALLACE'S MALAY WORLD

When naturalists point to maps of the ancient Sunda Peninsula and proclaim, “That’s the Malay world!” Their claim is totally understandable, since Malay was once the business language of maritime trade, used by merchants who came to the region in search of cloves, nutmeg, and sandalwood. In that sense, the term Malay world was, and remains, primarily a linguistic label for the region.

Some scholars, however, take a more imaginative approach. Rather than engaging closely with the evidence, they spend years developing speculative ideas, sometimes for as long as seven years, based on the assumption that everyone in the region is somehow “genetically Malay,” a concept that is itself ambiguous and problematic.

The Javanese | Siamese could just as easily declare, “That’s the Javanese | Siamese world!” Culturally speaking, this might even be a more accurate notion—though one that would no doubt leave certain scholars feeling rather disheartened.

When Indonesia shook off the Dutch, they chose Malay as the national language. The choice was made not because the Javanese majority was weak, but because simple, everyday Malay, the traditional trade language of the region, could help gelatinize the many linguistic tribes of Indonesia pretty quickly and easily. So the choice of officiating Malay as the national language was just more economical.

- Kere ▷ Stress ▷ Khilaf

- Kere ▷ Stress ▷ Tobat

- Kerja ▷ Kerja ▷ Kerja ▷ Duit

- Kerja ▷ Duit ▷ Gacha ガチャ

- Kerja ▷ Duit ▷ Ngesimp ▷ Nabung

- Makmur ▷ Ngesimp ▷ Hepi ▷ Nikah ▷ Samawa ▷ Sehat

- Sharing Gan ▷ Ngesimp ▷ Cerdas

- Menjadi manusia yang berdikari

เอาอะไรมาไม่เป๊ะ

— มุสาสื่อสารเชิงจิ้น (@Error309) April 9, 2025

“ทุงสะเทวี” ทรงพาหุรัด ทัดดอกทับทิม อาภรณ์แก้วปัทมราค ภักษาหารอุทุมพร (มะเดื่อ) พระหัตถ์ขวาทรงจักร พระหัตถ์ซ้ายทรงสังข์#หลิงหลิงคอง #LingLingKwong pic.twitter.com/DNg47XTjZG

MALAY AS VULGAR JAVANESE

A simpler way to think about it: Malay is basically mixture of vulgar Javanese and middle Javanese. Kind of like how French is just vulgar Latin.

For example, the phrase ‘I am going home' can be rendered in Javanese in three different flavors: Ngoko, Madya and Krama.

- Modern Malay (everyday speech)

- Aku = I

- balik = go home

- Ngoko (vulgar, informal, everyday speech)

ꦲꦏꦸ ꦩꦸꦭꦶꦃ

Aku mulih.5- Aku = I

- mulih = go home

- Madya (middle level, polite)

ꦏꦸꦭ ꦤꦸꦗꦸ ꦩꦸꦭꦶꦃ

Kula6 nuju7 mulih.- Kula = I (polite)

- nuju = going/on the way

- mulih = go home

- Krama (formal, highly polite, courtly speech)

Kula badhé wangsul.- Kula = I (polite)

- badhé = will / intending to

- wangsul = go home (polite / refined term)

- ‘Everyone' according to Asal Usul Melayu, Induknya Di Benua Sunda: the Filipinos, the Champa people, the Siamese (but not the Thais), the Javanese, the Sumatrans, the Borneans (including @borneadayak6725), and the folks in present-day Thai-Malay peninsula.

Zaharah Sulaiman, Wan Hashim Wan Teh, Nik Hassan Shuhaimi Nik Abdul Rahman (2016) Sejarah Tamadun Alam Melayu: Asal Usul Melayu, Induknya di Benua Sunda, UPSI Press, Tanjung Malim.

Cox's opinion seems particularly relevant here: The problem with today's world is that everyone believes they have the right to express their opinion and have others listen to it. The correct statement of individual rights is that everyone has the right to an opinion, but crucially, that opinion can be roundly ignored and even made fun of, particularly if it is demonstrably nonsense.

For a more serious read, see M. E. Phipps, B. P. Hoh, S. Oppenheimer, M. Mansor-Clyde, F. Aghakhanian (2018) Rebutting Zaharah Sulaiman on Malay genes second oldest in the world, Malay Mail, 4 August 2018.

Phipps's disappointments are reflected in the following words: . . . In Malaysia, archaeological and genetic research have been (mis)used to construct a pseudoscientific narrative of the antiquity of Malay genes, which claims that the Malays are one of the oldest distinct populations after human dispersal Out of Africa and that they were the progenitors of the Greeks and Chinese. The key arguments are laid out in a book that is published by a University Press (Zaharah et al. 2016). The proponents of this pseudoscience have presented their ideas in public forums for more than a decade, but in Bahasa Malaysia and it was not until 2018 that members of the Human Genome Project have spoken out publicly against the misinterpretation of their work . . .

Although Wallace (1869) divided the Malay Archipelago into five blocks: (a) the Indo-Malay group (b) the Timor group (c) the Celebes (d) the Moluccan group (e) the Papuan group, he named these blocks collectively as the Malay Archipelago since the the Malay language is the greatest common factor in the region, linguistically speaking: . . . if we look at the globe or a map of the Eastern hemisphere, we shall perceive between Asia and Australia a number of large and small islands, forming a connected group distinct from those great masses of land, and having little connexion with either of them . . . it is inhabited by a peculiar and interesting race of mankind - the Malay, found nowhere beyond the limits of this insular tract, which has hence been named the Malay Archipelago . . .

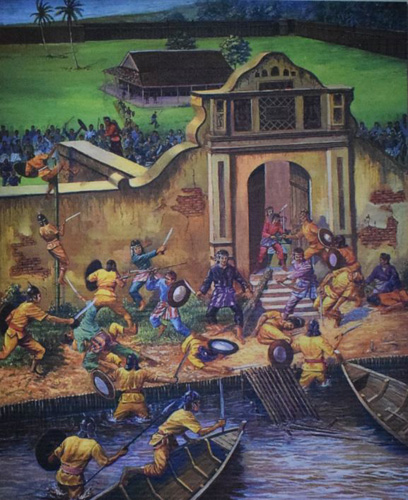

- Although the Kedahans fought to defend Kacapuri from the Siamese incursion, the city was eventually sacked. Sultan Ahmad Taj al-Din Halim Shah II was forced to flee to Penang in search of refuge.

When his father ceded Penang to the British in 1786, he could not have foreseen that one day the island would serve as a sanctuary for his sons and other members of the royal family. In 1821, Crawfurd was sent to Bangkok to persuade the Siamese administration to restore the Sultan Ahmad as the ruler of Kedah, but Crawfurd was told to hand the Sultan over to them instead and the annual payment of 10,000 Spanish dollars should be remited to the Siamese governor in Penang. Crawfurd refused.

- The data point is off by seventy-two years, as Sultan Muhammad Jiwa Zainal Adilin II died in 1778. While a small margin of error—perhaps a few years—is generally acceptable in historical research, a discrepancy of this scale is difficult to reconcile, especially for a scholar of Malay history. It highlights the importance of verifying dates carefully before forming conclusions, even when a statement is offered verbally and spontaneously in an interview.

- Apparently, the easiest way to escape the poverty trap is summed up in the

Tham-ngaan ทำงาน Thai ad by ThaiHealth (สสส.), featuring Saicheer Wongwirot (2005).

- Poor จน

- Stressed เครียด

- Drink ดื่มเหล้า

- Poor จน

- Stressed เครียด

- Stop drinking เลิกดื่มเหล้า

- Work ทำงาน

- Work ทำงาน

- Work ทำงาน

- Collect money เก็บเงิน

- Work ทำงาน

- Collect money เก็บเงิน

- Pay debt จ่ายหนี้

- Work ทำงาน

- Collect money เก็บเงิน

- Get educated!!!!! ได้เรียน

- Life stabilized แน่กิน

- Help others ช่วยเหลือ

- Happy

- Loved by your spouse

- Happy family

- Healthy

- Teach others

- Improve your community

- Smart

- Improve your country

The country of the Chakri kings and the Ayutthaya kings has been known to outsiders as Siam for centuries. For instance, on 20 November 1407, the Ming court received a mission dispatched by เจ้า นคร อินทราชา Chao Nakhon Intharacha 昭・祿羣・膺哆囉諦剌 and Zhu Di warned the Siamese king 暹羅國王 not to disturb the newly formed state by Parameswara.

(永樂五年冬十月)辛丑・暹羅國王昭・祿羣・膺哆囉諦剌,遣使奈婆即直事剃等奉表貢馴象、鸚鵡、孔雀等物。賜鈔幣、襲衣。命禮部賜王織金文綺紗羅表裏。 先,占城國遣使朝貢既還至,海上颶風漂其舟至湓亨國。 暹羅恃強凌湓亨,且索取占城使者,羈留不遣,事聞于朝。又,蘇門答剌及滿剌加國王並遣人訴暹羅強暴發兵,奪其所受朝廷印誥,國人驚駭不能安生。 至是賜敕諭昭・祿羣・膺哆羅諦剌曰:占城、蘇門答剌、滿剌加與爾,均受朝命比肩而立,爾安得獨恃強拘其朝使,奪其誥印。 天有顯道福善禍淫,安南黎賊父子覆轍在前,可以監矣。 其即還占城使者及蘇門答剌、滿剌加所受印誥,自今安分守禮,睦隣境,庶幾永享太平。夜,月犯軒轅南第五星。

In 1939, however, under the government of Plaek Phibunsongkhram, the country was renamed Thailand, to emphasize national identity and independence. Between 1945 to 1949, the name was briefly reverted to Siam after the War, then changed back permanently to Thailand in 1949.

The term Siam/Syam is derived from Sanskrit. In the Indic lexicon, Syama श्याम denotes a dark complexion, a characteristic often referenced by Thai's neighbors (Khmers, Burmese, Vietnamese, Chinese) to distinguish the melanin content in the epidermis. The term was also adopted by Europeans, and it appears to have been non-derogatory even from the Thai perspective. Internally, however, the Thai people do not refer to themselves as Siamese; they use khon Thai (Thai person) or chaao Thai (Thai citizen) instead.

- Following the Vaka-i Hayriye incident (the purge of the Janissary corps in 1826), Mahmud II introduced a dress code reform in the Ottoman State, replacing traditional turban wear with the fez. In the Malay world, the sarık or turban was the traditional headwear of kings and noblemen in the Johor-Riau-Lingga universe (and also in Aceh), such as Sultan Hussein of Singapore. The adoption of the fez (songkok or muak-khaek หมวกแขก) as customary Malay headwear occurred much later. For instance, Sultan Abu Bakar of Johor (d. 1895) is depicted in a marble statue wearing a sarık or turban.

- Although mulih ꦩꦸꦭꦶꦃ is absorbed into Malay lexicon as pulih ڤوله, it is not no longer used in modern Malay or at least in everyday Malay to mean ‘returning (home)'. Instead it now describes the restoration of something to its original or base condition, e.g. sedang pulih (body is recovering).

- Kula ꦏꦸꦭ is usually buried in Malay dictionary and old manuscript (e.g. Manatah janji paduka betara dengan kula . . . in Sejarah Melayu) and not triggered in everyday speech. For example, see Wilkinson (1901), p. 550. However, the kula is the root word of a common Malay word: Keluarga = Kula कुल + warga = family members. Ku or aku is apparently a truncated version of kula. Other variations of aku are: anaku, maku, inaku, kaku, panaku, etc. The word can also be combined with vamsa वंशम् to form kulavamsa, again a reference to members of a family.

See kaum keluwarga in Hikayat Gul Bakawali. Siti Hawa Hj. Salleh (1997) Hikayat Gul Bakawali (berdasarkan nashkah Hindi terjemahan al-Marhum Syekh Muhammad Ali bin Ghulam Hussin al-Hindi), Fajar Bakti, Shah Alam.

- Nuju ꦤꦸꦗꦸ is tuju توجو in modern Malay. Its meaning is exactly identical in Middle Javanese and modern Malay, both nuju and tuju mean heading for, making for, aiming at, pointing towards. See Wilkinson (1901), p. 197.

Comments