The three sho'ishaga in the Hobenpon

The first line in the Hobenpon chapter is a contextualizing paragraph

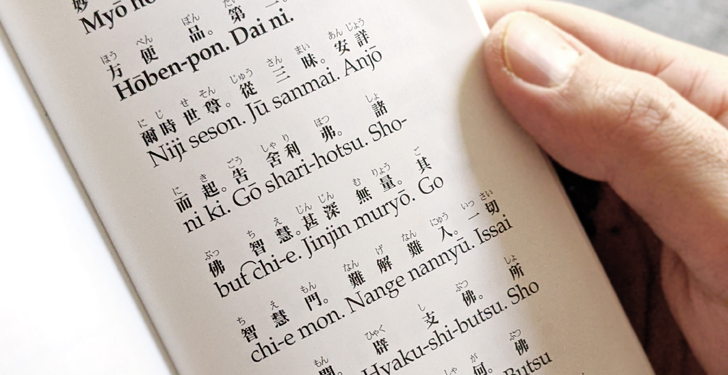

爾時 ,世尊 從 三昧 安詳 而起 。

which can be approximately translated as: At that time 爾時, Siddhartha Gautama 世尊 rose serenely 安詳而起 from 從 his meditation 三昧.1

He then turned his disciple Sāriputta2 舎利弗, and expounded the first sho'ishaga 所以者何.

The opening sho'ishaga

Sāriputta was asked: The wisdom of the Buddhas is profound and immeasurable. The gateway to their wisdom is difficult to understand and difficult to enter. None among all the Sāvaka-bodhisattvas or Pacceka-bodhisattvas can comprehend it.3 And why is this so?

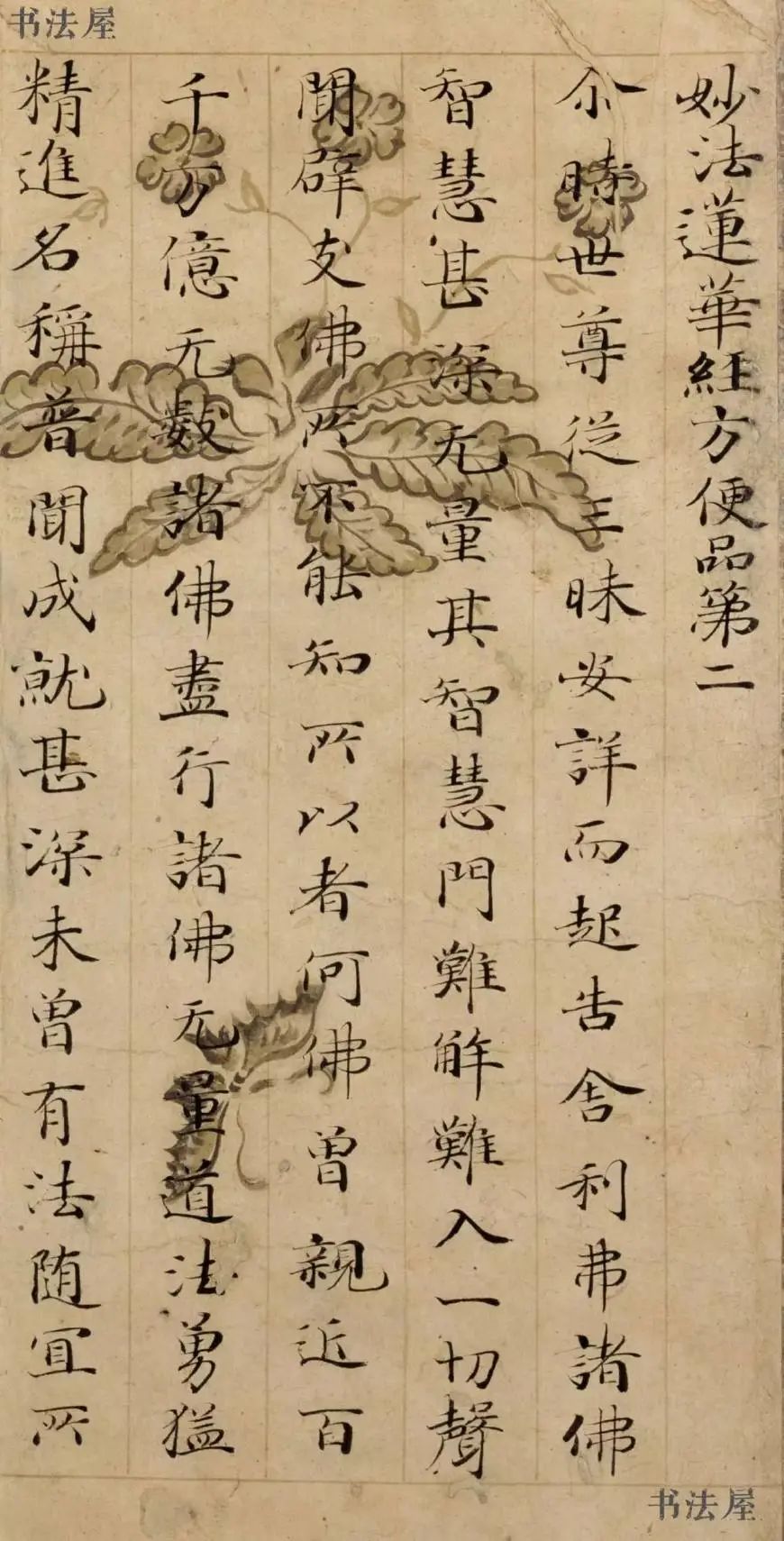

告 舎利弗 :諸 仏 智慧 ,甚深 無量 。其 智慧 門 。難解 難入 。一切 聲聞 辟支 仏 。所不能知 。所以者何 ?

仏 曾 親近 百千萬億 無數 諸仏 。盡行 諸仏 無量道法 。勇猛精進 ,名稱普聞 ,成就甚深 。未曾有 法 ,隨宜所說 ,意趣難解 。

Because the Buddha has personally approached and served about \(10^{11}\) Buddhas, and fully practiced all the immeasurable teachings and ways of those Buddhas. With great courage and diligence, his name has become universally known. He has perfected the profound and unprecedented Dharma, and teaches according to what is appropriate, yet his intent is difficult to grasp.4

The Tathāgata sho'ishaga

Sāriputta was then given the second question: Since I attained Buddhahood, I have used countless skillful means, various causes and conditions, analogies, and expressions to broadly teach the Dharma. Through innumerable expedient means, I lead sentient beings, freeing them from their attachments. And why is this so?

舎利弗 。吾 從 成 仏 已來 。種種 因緣 。種種 譬喻 。広演言教 。無數 方便 引導眾生 。令離諸著 。所以者何 ?

如來 方便 知見 波羅蜜 。皆已 具足 。

舎利弗 。如來 知見 。広大深遠 。無量無礙 。力無所畏 。禪定解脫 三昧 。深入無際 。成就 一切 未曾有 法 。

舎利弗 。如來 能種種分別 。巧說諸法 。言辭柔軟 。悅可眾心 。

舎利弗 ,取要言之 ,無量無辺 未曾有 法 ,仏 悉 成就 。

Because the Tathāgata has already perfected the Perfection of Skillful Means, of wisdom and insight. The insight of the Tathāgata is vast and deep, boundless and unobstructed. His power, fearlessness, meditation, liberation, and samādhi reach deeply into the infinite. He has fully achieved all dharmas that are unprecedented. The Tathāgata can distinguish and explain all things with skill and precision. His words are gentle and pleasing, delighting the hearts of the multitude. To put it briefly: The Buddha has completely perfected all dharmas that are immeasurable, boundless, and unprecedented.

The concluding sho'ishaga

Sāriputta was then given a rather sudden concluding pause: There is no need to say more. And why is that?

止 ,舎利弗 。不須復說 。所以者何 ?

仏 所成就 ,第一 、希有 、難解之法 ,唯 仏 與 仏 ,乃能究盡 諸法實相 。所謂諸法 :如是 相 、如是 性 、如是 體 、如是 力 、如是 作 、如是 因 、如是 緣 、如是 果 、如是 報 、如是 本 末 究 竟 等 。

Siddhartha Gautama ended the explanation with the rhymic decanyoze5: The Dharma realized by the Buddha is exceedingly rare and profoundly difficult to grasp. Only a Buddha, in communion with another Buddha, can fully comprehend the true nature of all phenomena — their

- Nyoze 1: projections and manifestations,6

- Nyoze 2: inherent properties,6

- Nyoze 3: structures and geometries,6

- Nyoze 4: energy levels and force fields,7

- Nyoze 5: functions and executions,7

- Nyoze 6: causes,8

- Nyoze 7: boundary conditions,8

- Nyoze 8: results,8

- Nyoze 9: karmic consequences,8

- Nyoze 10: the ultimate relationship between inputs and outputs9

et cetera, et cetera, et cetera.9

- Sanmai 三昧 is a phonetic approximation of samādhi, meaning the state of deep meditation. In Sanskrit, the word means union or integration, and it is created by joining sama (together), ā (a prefix) and dha (to place). Note that the final i vowel is not rendered in the Chinese approximation (i.e. 三昧 ≈ samādh, alternative approximations are 三摩提, 三摩地, etc). In English, both samādh and samādhi are captured by OED, but the former simply means the tomb of a holy man or yogi who is assumed to have achieved samādhi rather than to have died, e.g. in Asiatick Research (1828) XVI, p. 39, we have: A temple, sacred to the deity whom they worship, or the Samādh, or shrine of the founder of the sect, or some eminent teacher.

- Sāriputta is the first disciple of Siddharta Gautama. He is technically the St. Peter in Buddhism. His name was invoked 6 times in the Hobenpon abridged by Nichiren Shōshū. The invocation count is 52 times in the full version as the version used in the Nichiren liturgy is a truncated version.

- Sāvaka 聲聞 and Pacceka 辟支 are confusingly addressed as buddha 仏. It is clear from the context that they are not buddha, but semi-buddhas or bodhisattvas 菩薩. The alternative names for these groups of bodhisattvas are 聲聞菩薩 (Shōmon) and 緣覺菩薩 (Engaku). The phonetic approximations of these deities clearly indicates that their Sinic names are transcribed from texts written in Pali and not Sanskrit. Curiously, Siddhartha Gautama links two facts in the opening sho'ishaga: that the Shōmon and Engaku did not attain full Buddhahood, and that they are unable to fully comprehend the Dharma or pass through the Gate of Wisdom. The alternative explanation we were often given is that the Bodhisattvas, out of deliberate and altruistic intent, chose to remain in a state of partial enlightenment, postponing full Buddhahood so they could assist others in attaining awakening first.

- The answer to the first sho'ishaga can be made more accessible to most people if we adopt the following approximation:

Look, folks, the wisdom of the Buddhas? It’s tremendous. Believe me, nobody’s seen anything like it—profound, absolutely immeasurable. The gateway? Very tough, very complicated. Not easy to get in, I’ll tell you that. And who understands it? Nobody! Not the śrāvakas, not the pratyeka-buddhas—no one can get it. Why? Because the Buddha—he’s the best, really—he’s worked with, personally, hundreds of thousands of millions of Buddhas. That’s right, countless numbers. He’s learned all their teachings—every single one. And he’s done it with courage, with unbelievable diligence. His name? Everyone knows it. It’s huge. He’s perfected the Dharma—deep, unprecedented, nobody’s seen anything like it. And he teaches it in a way that fits—perfectly. But here’s the thing—his intent? It’s tricky. Very tricky. Not easy to understand. But folks, it’s huge. Believe me.

- The decanyoze paragraph is to be recited and invoked three times during gongyō. Many texts incorrectly treated 等 as equality or consistency, for example, the decanyoze is given as:

. . . this reality consists of the appearance, nature, entity, power, influence, inherent cause, relation, latent effect, manifest effect, and their consistency from beginning to end . . .

in the Liturgy of Nichiren Daishonin's Buddhism, published by SGI Canada (2004, p. 21).

Also, in the revised liturgy booklet published by SGI in 2002, the size of Nyorai'juryōhon 如來壽量品第十六 is considerably reduced by about 75 percent (from 2018 characters to 510 characters), in which only the pentaglyph gathas 偈言 are retained.

The treatment given by SGI is not unlike how Nichiren Shōshū 日蓮正宗 treated their original Hobenpon, in which original text was optimized and reduced by 96 percent from 4918 characters to 293.

Hobenpon and Nyorai'juryōhon are the only two chapters recited during gongyō 勤行. The reason for emphasizing Nyorai'juryōhon over other chapters is very obvious since the same emphasis on the techniques of Tathāgata 如去如來 was given by Siddharta Gautama in the Hobenpon.

- Sō 相 refers to appearance or form — the way an object 體 (tai) manifests or projects itself to the perceiver, often in a reduced or partial dimension. For example, a double-cone can be sliced in various ways, each slice presenting a different sō, each with its own distinct characteristics or properties 性 (shō).

- Riki 力 and sa 作 are closely interrelated concepts. 力 represents the physical input — the energy or force applied — while 作 refers to the resulting output or work performed. The output is typically shaped by boundary conditions 缘, which emerge from the mutual interactions and relational projections between the objects 體 involved.

- In'enkahō 因缘果報 is the Buddhist way of explaining causality and karmic law. Given an input 因 and a set of boundary conditions 缘, a output 果 will arise. The outcome is then biophysically relayed and reported 報 to the perceiver. Technically both 果 and 報 are in the output domain, but the fruit 果 is an objective translation of the cause and boundary conditions, whereas 報 is the subjective perception of the outcome.

- 等 is clearly an adverb in text, it is equivalent to et cetera or and so forth in English. In fact, one can break down the tenth decanyoze into 如是本 (source), 如是末 (sink), 如是究 (search), and 如是竟 (complete), not unlike how 因缘果報 is broken into four nyoze's, since 如是因缘果報 is equally legit. However, doing so will increase the nyoze example count from 10 to 13.

Comments