The Gate of Drakodont

For decades, the precise location of Longya Men 龍牙門 remains a subject of dispute in the maritime history of Southeast Asia.

The earliest1 description of the place was given by a Yuan Chinese traveler named Wang Dayuan 汪大淵 (b. 1311, d. 1350?) and the text is usually2 parsed this way:

門以單馬錫番兩山

相交若龍牙狀

中有水道以間之

This arrangement is optimizable since Wang's delineation can be made clearer if the two mountains 兩山 are removed from the first line and added to the second line:

門,以單馬錫番(i)

兩山相交,若龍牙(ii)狀

門中有水道,以間之(iii)

The first description is relatively easy to handle. Since 門 men2 is a shorthand for 龍牙門, the first line essentially means: The insular gateway(i) was inhabited by the native people 番 not unlike that of Temasik 單馬錫. This line suggests that in the 14th century, the ancient Srivijaya kingdom remained a maritime power, spanning a vast hydrographic region across Southeast Asia, including the southern Malay peninsula, the east coast of Sumatra, and all the islands in between, similar to the Johor-Pahang-Lingga-Riau kingdom a few hundred years later.

The second and third lines describe some curious topographical features of the locale, probably observed first-hand by Wang in 14th century. Here, we opted to address them in isolation. The second line describes a set of entwining peaks 兩山相交(ii) which resembles the pointed appearance of dragon teeth 若龍牙3. In the third line, we were told by Wang that there is a navigable waterway 水道(iii) in the middle 中 of the insula. Braddell (1950) was able to readily suggest that the water body situated between Lingga and Singkep as a potential candidate that meets Wang's criterion. Braddell's proposal is the present-day Selat Lima.

Longya 龍牙 is an Indic loanword meaning phallus. The name likely refers to the double-phallic prominence, a distinctive seamark gradually emerging on the horizon, reassuring ships sailing towards Palembang that they were on the right course. This natural biphallic statue is now part of Gunung Daik3, and it is described as ‘bercabang dua' in the following poem:

Pulau Pandan jauh ke tengah

Gunung Daik bercabang dua

Hancur badan dikandung tanah

Budi yang baik dikenang juga

- To be exact, the name can also be located in Song records (c. 1225). Writing 125 years before Wang, the place was rendered as Lingya Men 凌牙門 by Zhao Rukua 趙汝适 (b. 1170, d. 1231) in A record of native states 諸蕃志. Zhao mentioned the place not as an independent native state but and an important seamark leading to Srivijaya. Here Srivijaya is a reference not to Palembang but likely present-day Pekanbaru.

三佛齊:間於眞臘、闍婆之間,管州十有五,在泉之正南。冬月,順風月餘,方至凌牙門。經商,三分之一,始入其國。 Srivijaya is located between Angkor and Java, and governs fifteen prefectures. It lies directly south of Quanzhou, and it takes more than a month with the winter winds to reach the Gate of Lingya. From here, about \(\frac{1}{3}\) of the traffic would eventually end up in Srivijaya.

It is important to note that Zhao did not personally visit the places he described. His book was the result of a painstaking compilation of information relayed to him by returning merchants. Unlike Zhao, Wang embarked from Quanzhou and visited some of the isles inhabited by the insular natives 島夷 of Southeast Asia, not once, but twice, in 1330 and 1337. He likely passed through Lingga on his way to Srivijaya.

Wang Dayuan 汪大淵 (1350) An abridged record of native isles 島夷志畧. For example, see the version edited by Fujita Toyohachi 藤田豐八 (b. 1869, d. 1929), printed by Luo Zhenyu 羅振玉 in 1915, reprinted in 1936 by Wengedian Bibliotheca 文殿閣書莊 in Taiwan. H. Friedrich, W. W. Rockhill (1911) Chau Ju-kua: His work on the Chinese and Arab trade in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, entitled Chu-fan-chï, Imperial Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg.

- The translation given by Rockhill (1915) apparently puts the two mountains 兩山 in the first line: . . . It says that this strait is bordered by two hills of the Tan-ma-hsi barbarian (fan) which look like dragons' teeth, with a water-way between them. See W. W. Rockhill (1915) Notes on the relations and trade of China with Eastern Archipelago and the coast of the Indian Ocean during the fourteenth century, T'oung Pao 16(1), pp. 61 - 159.

The lines quoted by Lin Wo Ling 林我鈴 (b. 1911, d. ?) was: 門以單馬錫番兩山,相交若龍牙狀,中有水道以間之 . . . 男女兼中國人居之 . . . 以通泉州之貨易,皆剽竊之物也. Lin Wo Ling 林我鈴 (1999) Long-ya-men re-identified: A historical geography study of the two important junctions in the ancient Nanhai sea routes 龍牙門新考:中國古代南海兩主要航道要衝的歷史地理研究, South Seas Society, Singapore. See pp. 17-18. Lin was apparently able to break the line into . . . 兩山相交 . . . but he quoted the passage with the incorrect punctuation anyway (see pp. 17, 152, 156).

- The name can be decomposed into two parts. The first part, longya 龍牙, is the transliteration of the Malay word lŋg (لغݢ). The second part, men 門, is to taken literally as the gateway or portal, usually as an penultimate locale to mark the proximity of the final destination.

Earlier, Groeneveldt (1876) equated the word men 門 with ‘strait'. Interestingly, the location of the Groeneveldt's proposed Lingga Strait (northwest of Palembang, between Lingga and Bintan) was not able to match the Lingga-Karimun route highlighted by Wang (1350), which is broken into Selat Berhala and Selat Durian by modern hydrographers. Wang's intrainsular waterway (中有水道以間之) is most likely Selat Lima.

Seemingly overlooking the Indic influence on the region, Groeneveldt argued that the Chinese transcription of Lingga was both phonetically and semantically accurate.

W. P. Groeneveldt (1876). Notes on the Malay archipelago and Malacca, compiled from Chinese sources, W. Bruining, Batavia. See p. 79. Without realizing that Fei's Lingga entry was heavily modeled after Wang, Groeneveldt quoted Fei (1436) for his entry on Lingga and downplayed the value of Wang's travelogue by writing: . . . very few, and most insignificant extracts from it, by which circumstance some doubt is thrown on the value of this little book . . .

- In the Overall Survey of the Star Raft 星槎勝覽, Fei Xin 费信 repeated Wang's description, albeit more thrifty and poetic in his usage of words: 山門相對,若龍牙狀,中通過船 (opposing peaks, drakodont-shaped, mid-sailable).

The description given by Fei's comrade in the Overall Survey of Ocean's Shores, however, is completely different. Ma Huan 馬歡 (b. 1380?, d. 1460?) mentioned the Gate of Longya simply as a significant seamark for those sailing to Melaka: 自占城向正南,好風船行八日到龍牙門,入門往西南行二日可到 (From Champa, sailing directly south with favorable winds, it takes eight days to reach the Gate of Longya. Upon entering this locale, sailing southwest for another two days will bring you to Melaka).

Fei's description is problematic if we consider the two seemingly conflicting lines, also found in the Overall Survey of the Star Raft: (a) 龍牙門,在三佛齊之西北 (b) 東西竺,其山與龍牙門相望. Fei's first remark is consistent with the line adapted from Wang. The second remark, on the other hand, is consistent with Ma's description but it contradicts with Fei's entry on the Gate of Longya.

- Daik is likely the Chinese name given to the mountain. Hakka pronunication of 大一 is Tai-yit. In 2017, many wooden structures in Kampung Cina Daik was consumed by fire.

山若纏若斷 (connected yet broken) is a apparently a description of a mountain range. Shown above is a view of Ledang mount taken from a distance 30 km away.

- Wang cross-referenced the location of Lingga with that of Panchur (or Barus) with the following line: Panchur 班卒 can be found behind the Gate of Lingga 地勢連龍牙門後。山若纏若斷,起凹峯而盤結,故民環居焉 (Panchur can be found in the terrain behind the Gate of Lingga. The mountainous range is continuous yet broken, these alternating elevations are intricately intertwinned, necessitating people to settle around these mountainous networks).

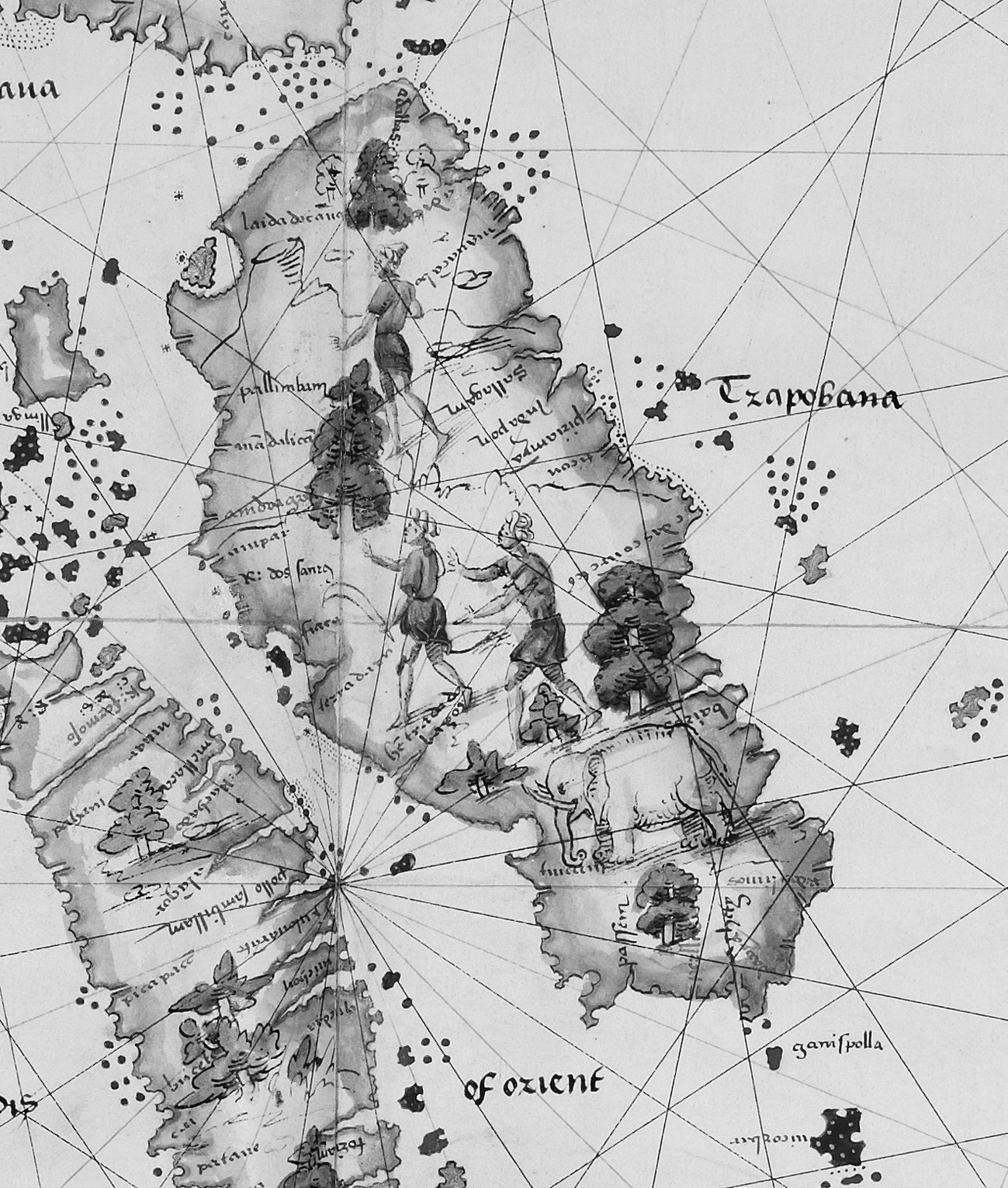

Barus (Panchur 班卒) in Jean Rotz's map. Barus was mentioned, alongside Minangkabau, by Barros in Décadas da Ásia (1552).

- See W. D. Barnes (1911) Singapore Old Straits and New Harbour, JSBRAS 60, pp. 25 - 34. See also R. Braddell (1950) Lung-Ya-Men and Tan-Ma-Hsi, JMBRAS 23(1), p. 43.

- W. H. Moreland (ed. 1934) Peter Floris: His voyage to the East Indies in the globe 1611 - 1615: The contemporary translation of his Journal, Hakluyt Soceity, London.

In this morning wee had Pulo Pon juste att our stearne, and towards evening sawe the Iland of Linga sticking oute with his hares eares.

Moreland noted that Floris's description of the double-peak was apparently influenced by Linschoten's Reys-Gheschrift. In Chapter 27, Linschoten refers to a hill on Lingga which has two summits like the ears of a hare, forming a conspicuous seamark.

See Iohn Wolfes (1598) Iohn Huighen van Linschoten his Discours of voyages into ye Easte & West Indies, London.

- T. R. J. Popplewell (1999) Admiralty sailing directions: Indonesia pilot, Volume 1, 3rd edition. UK Hydrographic Office, Somerset. The first and second editions were published in 1975 and 1996, respectively. Figure 24 (p. 106) in Lin (1999) is likely a Gunung Lingga view replicated from the first or second edition. In the same page, Lin reproduced the another Gunung Lingga view (with more prominent rabbit's ears), purportedly seen by HMS Osterley and HMS Albion in 1762 (Albion was wrecked in 1765, Osterley was last recorded in 1770). See also C. H. C. Langdon (1886) The China Sea Directory Vol. 1, 3rd ed. Hydrographic Office, Admiralty, London. In p. 112, we have a description of Lot's Wife:

. . . a rock about 6 feet above high water, lying immediately off the pitch of Blayer point . . .

Wang (1350) was apparently referring mountains and not some dwarf stone pillars. For instance, Gunung Daik and Gunung Bintan are approximately 4,000 feet and 1,000 feet, respectively. Gunung Bintan can be seen from a distance of 60 kilometers, while Gunung Daik is visible from 120 kilometers. In 2005, a 6-meter replica, purported to be the seamark described by Wang, was commissioned by Singapore to commemorate the 600th anniversary of Zheng He's maiden voyage (1405). A mix-up between imperial and SI units likely occurred during the planning of the replica.

- Longyamen was memorialized in the History of Yuan 元史 in the following entries: (a) 卷二十七・延祐七年・九月・甲辰・雲南木邦路土官紿邦子忙兀等入貢,賜幣有差。遣馬扎蠻等使占城、占臘、龍牙門,索馴象。以廪藏不充,停諸王所部歲給 On the day of Jiachen, in the ninth month of the seventh year of Yanyou (30 October 1320), the natives of the Hsenwi state in Yunnan, represented by Mangγud (the son of Tai Pong) etc, came to offering tribute and were granted rewards in varying amounts. Missions, led by Majarman etc, were dispatched to Champa, Khmer, and Longyamen to procure tamed elephants. Due to insufficient grain reserves, the annual provisions for the princes were suspended. (b) 卷二十九・泰定二年・五月・癸丑・龍牙門蠻遣使奉表貢方物 On the day of Guichou, in the fifth month of the second year of Taiding (15 June 1325), the natives of Longyamen sent envoys to present a memorial and tribute of local products.

Comments