The tuah-tuha kerfuffle

“Twah” in old Javanese literature

The word “tuah” is phonetically similar to “twah”, although they may look a bit different orthographically. Curiously the disimilarity is true only when Roman/Javanese script is used, for in Jawi script, they are completely identical since “u” and “w” share the same wa-glyph (و).

Now, the word “twah” can be found in The English version was published by Zoetmulder himself in 1982. Darusuprata and Sumarti Suprayitna worked out an Indonesian version and got it published in 1995.

• P. J. Zoetmulder (1982) Old Javanese-English Dictionary (with the collaboration of S. O. Robson), Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague.

• P. J. Zoetmulder, Darusuprata, and S. Suprayitna (1995) Kamus Jawa Kuna-Indonesia, Gramedia Pustaka Utama, Jakarta.

The word “twah” can be found in p. 1339:

twah (JwB/ModJ toh, GR:) bercak bawaan, bercak hitam pd kulit. birthmark, black spot on the skin.

GR: is an abbreviation of J. F. C. Gericke, T. Roorda (1901) Javaansch-Nederlandsch Handwoordenboek. 2 vols, Leiden, Amsterdam. JwB/ModJ is a shorthand for “modern Javanese”.Zoetmulder (1982), although he was only able to furnish one quotation for this entry and the book quoted was Tantu Panggĕlaran is an old Javanese prose. Theodoor Pigeaud (1899 - 1988) translated and annotated the text (using five manuscripts, A, B, C, D, and E) into Dutch in his doctoral thesis and the result was published as: T. G. T. Pigeaud (1924) De Tantu Panggĕlaran: Een Oud-Javaansch prozageschrift, uitgegeven, vertaald en toegelicht, PhD Thesis, Leiden University.

Recently S. O. Robson and H. Sidomulyo jointly worked out a new English version. S. O. Robson and H. Sidomulyo (2021) Threads of the unfolding web: The old Javanese Tantu Panggĕlaran, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore.Tantu Panggĕlaran, a creation myth story of Java insula, composed in old Javanese:

. . . Tinahapnira (Parameçwara) tang wai Kālakūṭa; mahirĕng gulu bhaṭāra kadi twah rūpanya. Matangnyan bhaṭāra Guru mangaran bhaṭāra Nīlakaṇṭa, apan ahirĕng kadi twah . . . (Pigeaud, pp. 64 - 65)

Pigeaud (1924) tells us that in Manuscript D and E, the word twah is spelt as “toh", and in Manuscript B, it was spelt as “wwah". Both “toh" and “wwah" can be found in Zoetmulder but their meanings are unlikely to fit the description of Parameswara in Tantu Panggĕlaran, for “toh" means Zoetmulder (1982), p. 2027:

toh II: stake (in game, gambling, wager, competition, combat), main stake (in combat) > the peson on whom one relies as the main or sole support.

bwat toh: gambling

amwat toh: to gamble

Kamus Dewan (1970):

toh I: Jk titik atau cacat pada kulit (hitam atau kemerah-merahan warnanya).gambling stake or wager and “wwah" means In modern Javenese, woh or woh-wohan means fruit(s). They are Javanese cousins of buah or buah-buahan, modern Malay word for fruit(s).fruit.

The English description (Robson and Sidomulyo, 2021) of how Parameswara got his twah, is given as follows:

. . . He (Parameśwara) drank the Kālakūṭa water, and the Lord's neck became black, looking like a birthmark. For this reason Lord Guru is called Lord Nīlakaṇṭa, because his neck is black like a birthmark . . . (Robson and Sidomulyo, p. 15)That “twah” or “tuah” is a reference to birthmark is no longer common in modern Malay usage, for example, it is not captured by the voluminous Salmah Jabbar, Nor Azizah Abu Bakar, Noresah Baharom, Fadilah Jasmin (2021) Kamus Dewan Perdana, Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, Kuala Lumpur.Kamus Dewan Perdana. Fortunately, in the good old Teuku Iskandar (1970) Kamus Dewan, Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, Kuala Lumpur.Kamus Dewan, we have the following entries (curiously under the third definition of “tuah” as “keistimewaan” or “exceptional” and labeled with “Br” by Teuku Iskandar, indicating that they are of Bruneian usage):

- Tuah berma: Tanda merah pada bayi ketika dilahirkan

- Tuah periuk: Tompok-tompok biru tua pada bayi ketika dilahirkan

Both tuah periuk and tuah berma describe birthmarks found on newborn babies, “berma” directly describes the color of the birthmark (as red spot), while “periuk” describes the size of the birthmark, since Mongolian spot (common name of tuah periuk), usually present itself as a group of large blue-gray patches on buttocks or sides of neonatals.

It is clear that tuah berma and tuah periuk directly inherited the Javanese usage of “twah” as birthmarks. What is not so clear here is the process of how the physical meaning of the word is dropped and overshadowed by its “positive” metaphysical connotation, since birthmarks can be culturally interpreted as auspicious or inauspicous. Given the role of Parameswara in Tantu Panggĕlaran, we can suppose that the black “twah” on his neck was culturally auspicious. This is reinforced by an additional paragraph was appended to explain his nickname literally the beloved black, nīla नील is mistakably a reference to black in this context, kaṇṭa is likely a description of birthmark-induced pleasantness, visio-culturally.Nīlakaṇṭa.

The (و-ه)-ligature in old Malay manuscripts

The و-glyph and ه-glyph (or ة-glyph) can be written conjointly, forming a distinctive double-loop ()-ligature. This ligature can thus be utilized to represent the following sounds:

- uh

- ut

- uah

- uat

- wah

- wat

For instance, in the following Instagram post, we give a real-world example of how the word “قوّة" (= kuat = Arabic/Malay word for strength and power) is handled by a modern Ahmed Adel Khater is a calligrapher based on Cairo, Egypt.lettering artist:

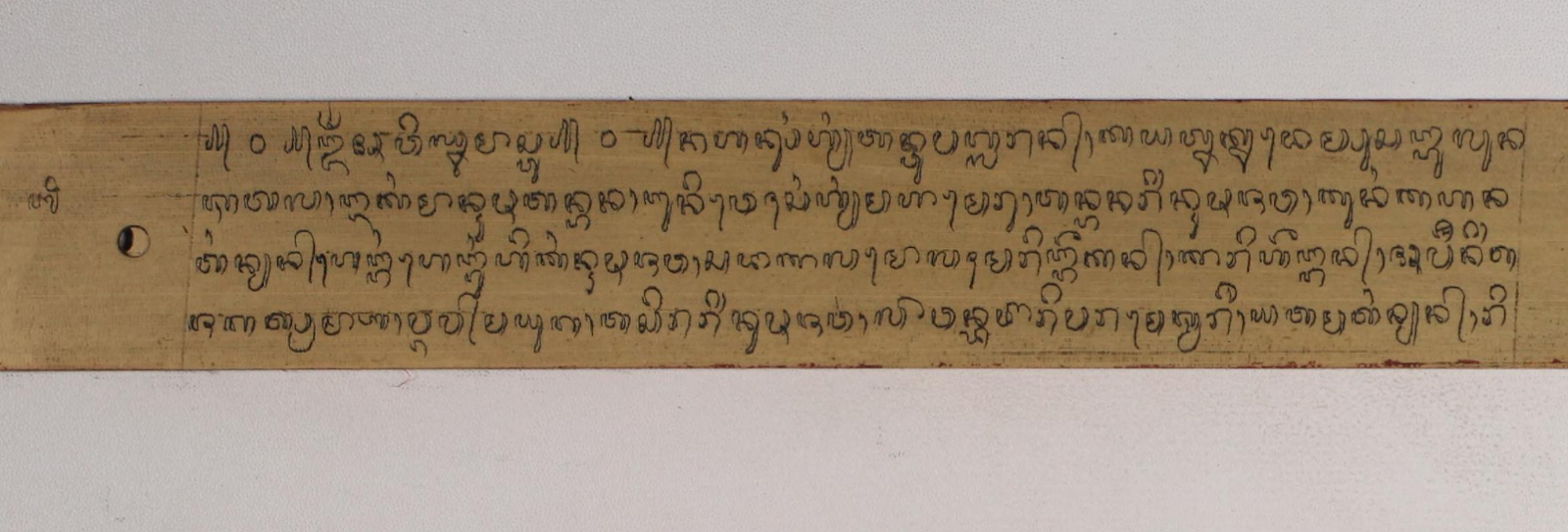

The same treatment can also be found in old Malay manuscripts. For instance, in Hikayat Hang Tuah (BL Or 16215), the following words conform to the double-loop ()-ligature.

- Laut

- Buat

- Bawah

- Buah

- Jauh

- Tuah

It should be noted that in BL Or 16125, “tuha” and “tuah” are handled differently from a orthographic standpoint. For instance, in folio f. 103r, the second syllable of “tuha” was given a special emphasis by the scribe since he spelt “ha" as “ها" (ha followed by concluding alif). Thus, we suppose that “tuha” and “tuah” must be semantically different to the scribe and the author of the book. Sometimes, the scribe was found to render “tuah” as “تواه” (alif followed a concluding ha). This observation is an additional proof that the word “tuah” is meant to be phonetically ended with a breathy value.

Comments