The medieval chronology of Malacca

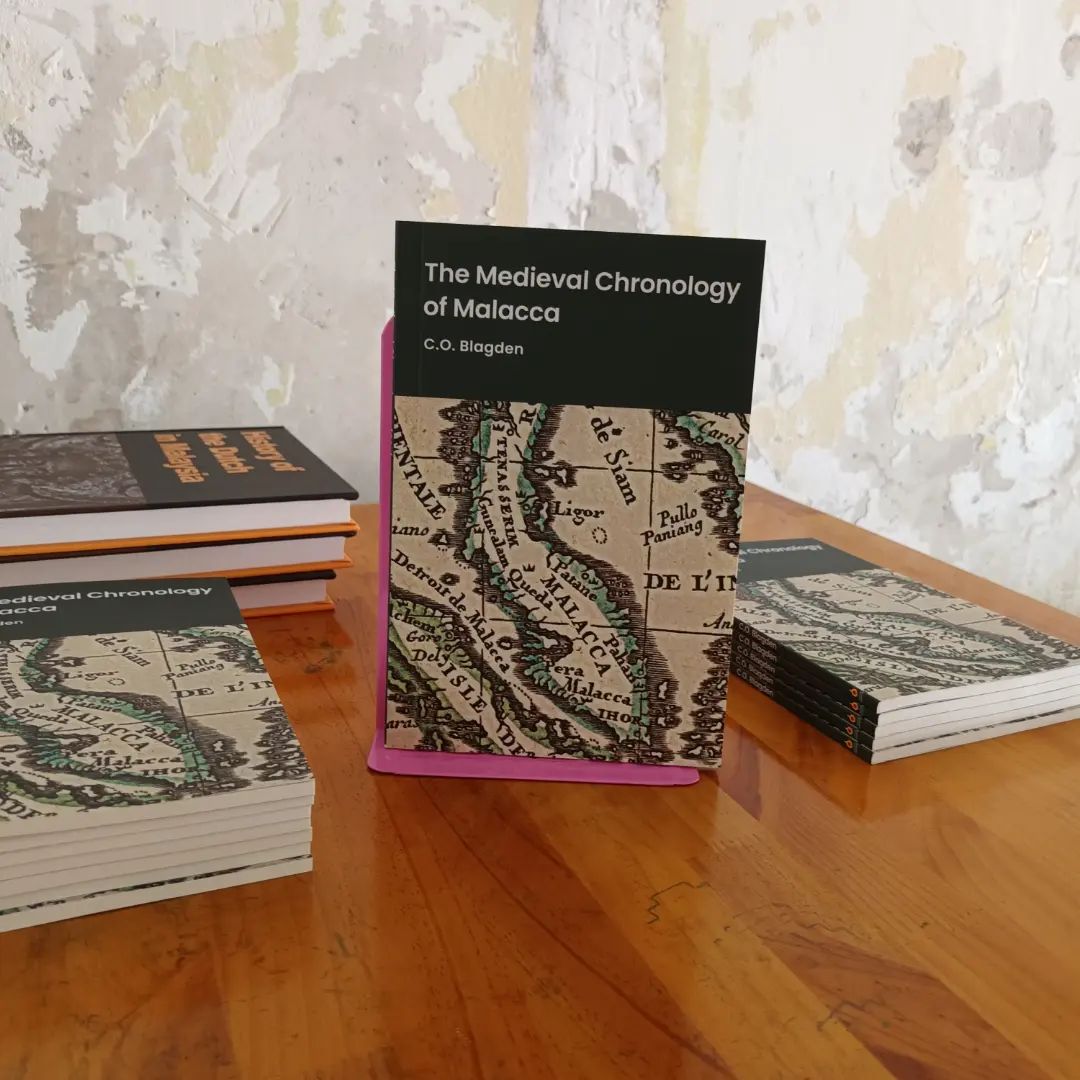

In 1897, Charles Otto Blagden (6 September 1864 – 25 August 1949) presented a paper entitled “Medieval chronology of Malacca" at the 11th International Congress of Orientalists (5 - 12 September 1897, Paris). This paper was recently printed as a small booklet by Nutmeg Books. In what follows, we reproduce the full text of Blagden's 1897 paper, using digitized text data from Bibliothèque nationale de France.

That Malay history is as yet in a very unsatisfactory state will be readily admitted by all who have taken the trouble to look into the subject. So far as the medieval period is concerned, it may be fairly said that what passes for history amongst the Malays consists mainly of a string of purely mythical legends, partly of native, partly of Arab but mainly of Indian origin, followed by and to some extent mixed up with anecdotic accounts of real Malay kings and kingdoms, in all of which there is much of ethnological interest, a great deal that is of value to the student of Malay customs, institutions and characteristics generally, but not a single reliable date and hardly a single fact that could enable one to fix the period concerning which the tales are told.

Unfortunately we are, in the Malay Peninsula, almost entirely deprived of that fruitful study of monuments and inscriptions which, in other Eastern countries, has been of such signal service in correcting the native traditions of history and in establishing a sound chronology, and it would seem that the foreign sources of history that could be used to check the Malay authorities are scanty, though they have not as yet been fully explored. Siamese and other Indo-Chinese chronicles, for instance, should throw some light on the history of the Malay Peninsula from the 13th to the end of the 15th century, if not also in earlier periods: but nothing of the sort seems to be accessible at present to the ordinary reader.

For the history of Malacca before its conquest by the Portuguese the principal sources are:

- The Chinese records contained in the Ying-yai Sheng-lan 瀛涯勝覽 (1416), the Hai-yu 海語 (1537) and the History of the Ming dynasty 明史 (1368-1643) of all of which translated extracts are to be found in Groeneveldt's Notes on the Malay Archipelago and Malacca (Essays relating to Indo-China, series II, vol. I, pp. 243-254);

- The Commentaries of Alboquerque, of which a translation by W. de G. Birch has been published, by the Hakluyt Society (see especially Vol. 3, pp. 71-84);

- The Sejarah Melayu, the well known native work, the preface of which gives indications that it dates from the early part of the 17th century but which contains internal evidence of having been at any rate in part composed at a somewhat earlier date.

The last named is the authority mainly followed by the Dutch historian Valentyn

(see JSBRAS 13, pp. 62-70) and also by later authors, such as Marsden and Begbie. It has been largely accepted as a historically trustworthy work, though Crawfurd in his History of the Indian Archipelago (Vol. 2, p. 374), and also in his Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands (under the heading “Malacca”), pointed out long ago that it was in several respects open to serious criticism.

The fact that it is considerably at variance with the earlier account of the origins of Malacca contained in the Commentaries of Alboquerque (and followed by the author of the tract published in JSBRAS 17, pp. 117-119, as well as some other Portuguese writers) must not be lost sight of in estimating the trustworthiness of these so-called “Malay Annals". The Commentaries of Alboquerque embody Malay legends current soon after the Portuguese conquest and therefore some two generations nearer to the events they profess to relate than the more detailed and elaborate accounts of the Sejarah Melayu, and to that extent the former may claim the greater weight as authorities.

Both however are based on the same precarious foundation of oral Malay tradition, and neither can lay claim to anything like chronological accuracy. In both a purely legendary story of the foundation of the town and state of Malacca leads up to a short list of the Rajas who reigned there within the few generations that preceded the advent of the Portuguese, the Sejarah Melayu merely giving a much fuller and more detailed account of their reigns, mixed up with a great deal of episodical matter, and also stating in some cases the number of years during which each Raja is supposed to have occupied the throne.

It is from these figures that the received chronology of Malacca during the medieval period has been compiled, and this calculation, supplemented apparently by other figures of equally doubtful authenticity, is the basis of the often repeated statement that the old Singapore was founded in 1160 and conquered by the Javanese of Majapahit in 1252, two dates which have been taken on trust so long, that one is almost surprised to find on what slender evidence they really rest, when we consider that they have been assumed as fixed points in almost all accounts of the history of the Straits Settlements and the Malay Peninsula.

The Chinese authorities already mentioned stand on an entirely different footing. They are contemporary records, very meagre, it is true, and also no doubt to some extent distorted by the point of view of the Chinese historian who sees in every trading enterprise or complimentary diplomatic mission a tribute to the exalted majesty of the Chinese Emperor.

But they are matter of fact documents containing definite dates and the only pity is that they do not add much to our knowledge of the internal history of the Malay states to which they refer. What is worth noting is that they do in the most remarkable way confirm the fact mentioned in the Sejarah Melayu of the existence of diplomatic relations between the Raja of Malacca and the Chinese Emperor.

The Malay author of course represents it as a correspondence between equals: the Chinese historian regards it from a totally different point of view, and makes the Malay Raja a very humble and loyal vassal. But the historical fact remains, well attested from both sources, that during the whole of the 15th century diplomatic relations and trade under the forms of embassy were continuously maintained between China and Malacca.

There is one point on which the Chinese and the Malay historian are widely at issue: the former makes Malacca a revolted vassal state of Siam (in which view he is supported by Alboquerque, who puts the emancipation of Malacca some ninety years before the Portuguese conquest), the definite recognition of its independence being attributed by the Chinese historian to a grant of regalia in 1405 by the Chinese Emperor.

The Malay scorns any such admission; according to him Malacca was never subject to Siamese supremacy in any form but held out successfully against all attempts made by Siam upon it. He admits a series of such invasions, in all of which he contends that the Siamese were uniformly unsuccessful.

At this distance of time it may be hazardous without more definite data to form any conjecture as to what actually was the course of history. The Siamese kingdom of Ayutthaya was itself but of recent creation (1350 AD) at the time of which the Chinese historian wrote. But it was preceded by other kingdoms in the same region and it may have inherited the reversion of some older Indo-Chinese claims of supremacy over the Malay Peninsula, which it attempted with more or less sucess to vindicate. It is needless to say that Malacca is by the Siamese themselves numbered as one of their tributaries in those days. But then so is Java where there would seem to be no foundation for the claim, but the vainglorious ambition of the Siamese.

The main purpose, however, of this paper is not to deal with the foreign relations or internal history of Malacca and the Malay Peninsula, but to point out to what extent the Chinese records can be used to check and correct the traditional Malay chronology, and by necessary inference to indicate the estimate which should be formed as to the trustworthiness of the latter.

Each of the three authorities already referred to gives us a list of kings and the comparative table below will show how far they differ from one another. The Commentaries of Alboquerque give no dates but indicate that a period of about a century covers the reigns that they enumerate. Both the Sejarah Melayu and the Commentaries give an account of the foundation of Malacca, but the two accounts differ (as has been already stated) in several material particulars. The Chinese historian of the Ming dynasty does not tell us how or when Malacca was founded. That its foundation took place in pre-Muhammadan days there seems no reason to doubt, though, as Crawfurd points out, Iskandar Shah, the founder according to the Sejarah Melayu, bears a Muhammadan name and title.

That however is not decisive, as the legend of its foundation has all the appearance of being mythical. The Commentaries make the founder one Parimicura, late of Palembang and Singapore, and represent Xaquendarsa his son as the second raja and the first convert to Islam. There is no reason to doubt that Xaquendarsa represents the same person as Iskandar Shah, though the two lines of tradition have diverged in their accounts of him.

The Chinese historian, however, finds Malacca Muhammadan in 1409, under the rule of a chief whom he styles Pai-li-mi-su-ra 拜里迷蘇剌, which title is probably the same as the Parimicura of the Commentaries.

Here are debateable points enough and to spare, but to return to the safer ground of the period immediately preceding the Portuguese conquest, it is noticeable that there is hardly any discrepancy in the lists so far as the last few kings are concerned. The Sultan Mahmud Shah whom Alboquerque expelled is indeed represented by two names in the Chinese list: but the second may well be intended to represent his son (styled Sultan Ahmad by the Sejarah Melayu and Prince of Malacca by the Commentaries) to whom, according to the Malay authority, Sultan Mahmud had delegated the actual administration of the state. According to Valentijn, who follows Malay sources, Mahmud came to the throne in 1477, while it appears from the Chinese records that his accession should be put some years later. He was a young man when his father Alaeddin died, poisoned according to the Commentaries at the instigation of the kings of Pahang and Indragiri.

Alaeddin, of whom little is said in the Sejarah Melayu, appears to have had a short reign and it is not surprising

therefore that he is not mentioned by the Chinese chronicler. No one can doubt that, so far as the names go, the Mang-su-sha and Wu-la-fu-na-sha of the latter are to be identified with Mansur Shah and Muzzafar Shah, the Marsusa, and Modalaixa of the Commentaries, respectively. Up to this point therefore the agreement between the three lists may be said to be practically complete.

The Chinese authority does not state that Wu-ta-fu-na-sha had just succeeded to the throne at the time of sending his embassy in 1456 and as no king is mentioned as having died since 1424, it may well be that the two names preceding his on the list are merely alternative titles of his own. This view is to some extent supported by a passage in the Commentaries from which it may perhaps be inferred that the name Mudhafar Shah was assumed by him somewhat late in his reign.

His predecessor according to the Sejarah Melayu was his brother Abu Shahid, who was slain after a brief reign of 17 months, which accounts for the absence of any reference to him in the other authorities.

So far everything seems plain enough, but as one goes further back the difficulties increase. Passing over the two names in the Chinese list which seem to be alternative titles of Muzzafar Shah, our sources then give us the following names as representing the next king, viz. Mu-kan-sa-u-tir-sha — Xaquendarsa — and Muhammad Shah, respectively. The last two, each by his own historian, are represented as being the first Muhammadan Raja of the state of Malacca. Mu-kan-sa-u-tir-sha on the other hand is represented as the son of Pai-li-mi-su-ra, in whose time acccording to the Chinese historian Malacca was already Muhammadan.

x

There would seem to be here a discrepancy which we cannot get over. The difficulty about the introduction of Muhammadanism may, however, be due to some confusion between this Raja and a predecessor of his. As to the difference in names. I have only a conjecture to offer: by a very slight change in one of the characters, Mu-kan-sa-u-tir-sha could be read Mu-kan-sa-kan-tir-sha, and it is just conceivable that this may represent a corrupt form of Muhammad Iskandar Shah, a name for which it is true there is no other authority but which would reconcile the conflicting traditions represented respectively by the Sejarah Melayu and the Commentaries. It is worth mentioning, too, that Bastian in his Geschichte der Indo-Chinesen, p. 365, writing presumably from Siamese sources, though he does not give his authority, states that one Sakanadhara, who made himself obnoxious to the Siamese by interfering with their trading vessels, was Raja of Malacca about the year 1418, the very period covered by the reign of this mysterious Mu-kan-sa-u-tir-sha in the Chinese record. The comparison of the three lists cannot be carried any further and it is noticeable that instead of names the Sejarah Melayu from this point onwards gives us nothing but titles without personal names or facts connected with them till we get to the legendary founder of the state, the Hindu Raja with the Muhammadan name.

But it is clear from the comparison, where comparison is possible, that the definite chronological data of the Chinese historian make short work of the long reigns of the received chronology.

A priori of course such long reigns are most suspicious, especially in an Asiatic country: as Yule in his Marco Polo (2nd ed., p. 263) pointed out, the average of 33 years ascribed to the reigns of the kings of Malacca indicates that the period covered by them according to the received chronology requires considerable curtailment. His conclusion is “that Malacca was founded by a prince whose son was reigning and visited China in 1411". That is, he accepts the view supported hy the Commentaries, and to some extent also by the Chinese historian, if we identify the Pai-li-mi-su-ra 拜里迷蘇剌 of the latter with the Parimicura of the former, that Malacca was founded about the end of the 14th century.

It is fair to point out that there is one possibility of error in the Chinese records worth mentioning. The name of the father may in some cases have been wrongly put for that of the son.

Thus Wu-ta-fu-na-sha may possibly represent Sultan Mansur ibn al-Marhum Muzaffar Shah and so on. But this would not help the Malay historian materially: it would only reduce the discrepancy, which amounts to a century or more, by the length of a single reign.

The received chronology, however, taken together with the traditions recorded in the Sejarah Melayu, and quite apart from comparison with extraneous sources, is intrinsically so extremely improbable that a simple inspection is almost enough to destroy all belief in its correctness. That the reigns of four generations of Rajas, from Sultan Muhammad Shah to Sultan Alaeddin Shah inclusive, could cover a space of 201 years is utterly incredible, and it seems to me extraordinary that such a palpably impossible chronology should ever have been taken seriously.

x

The Sejarah Melayu itself, if its evidence be worth anything, contains sufficient data to upset it. To take only one case, the story of the life of the great Bendahara Paduka Raja begins in the reign of Muzaffar Shah, when under the name of Tun Perak he helped to repel the attacks of the Siamese and became successively a Mantri and eventually Bendahara (the highest office in an ancient Malayan state, next to that of the Sultan) which office he retained throughout the reigns of Mansur Shah and Alaeddin Shah. And finally he was visited on his death bed by Sultan Mahmud, the last of the Malacca Rajas. Now according to the received chronology the life of this great officer of state would cover something like 130 years and his tenure of the office of Bendahara would exceed 100, which is manifestly absurd.

But the Sejarah Melayu, as its introduction proclaims, owes its inspiration to the national sentiments of the descendants of some of the leading chiefs who took a principal part in the affairs of Malacca during the period immediately preceding the Portuguese conquest. Besides being in great part what it professes to be, a history of the principal Malay states of those times, it is full of matter of a genealogical and personal interest and is far more likely to be correct in its accounts of the leading men of Malacca in the 15th century (for whose descendants in the 17th it was composed) than in matters of chronology. Malays are very fond of recalling the stories of their ancestors and many a village headman even can recount his pedigree for 5 or 6 generations back, though he could not tell his ownage, to say nothing of the date of his father's or grand-father's birth. There is therefore considerable probability in the view that the Sejarah Melayu contains, together with much mythical matter and many irrelevant details and episodes, a substantially true account of the principal Malacca chiefs of the period comprised between the establishment of Islam and the arrival of the Portuguese, or at any rate from about the beginning of the 15th century. Of course if it is to be considered untrustworthy even in this respect, then a fortiori the chronology clumsily deduced from it and from similar native chronicles, also falls to the ground : but I prefer to believe that facts of such great personal and family interest would be remembered fairly correctly , while the dates connected with them would very probably be left unrecorded and would be forgotten.

The probability that the foundation of Malacca, which is usually laid in the middle of the 13th century, must be put nearly a century and a half later, is supported by a certain amount of negative evidence.

Not one of the travellers, whose accounts have come down to our day and who visited these regions during the period in question, that is to say the 13th and 14th centuries, mentions Malacca at all.

Marco Polo, Odoric, Ibn Batuta are all alike silent on the subject. The case of the last named is no doubt the strongest argument, as his visit was the latest in point of time. Like the other travellers he spent some time in Sumatra, and if Malacca had been in the middle of the 14th century anything like the great emporium of trade which it certainly was in the 15th, Ibn Batuta would scarcely have failed to speak of it.

From the fact of his visit, moreover, an additional argument can be adduced in favour of the view that Malacca did not exist in his time. The state he visited was Samudra, otherwise The two places were distinct but not far apart and they were sometimes united in one state, sometimes governed by separate princes of one dynasty.Pasai, and the Chronicles of Pasai, which are extant in Malay, relate at somewhat greater length the same events as chapters 7 to 9 of the Sejarah Melayu. Now according to both these histories the founder and first Muhammadan Raja of that state was one Marah Silu, who on his conversion adopted the style of Malik-al-Salih. His son, according to the Pasai Chronicle, his eldest son according to the Sejarah Melayu, and his immediate successor according to both authorities was Malik-al-Dhahir.

It was this Malik-al-Dhahir, king of Pasai and Sumadra, who was Ibn Batuta's host in or about the year 1346; and a year or two later, on returning from China, Ibn Batuta visited him again and was present at the wedding of his son.

It seems probable therefore that Muhammadanism can hardly have been established in Pasai much earlier than the last quarter of the 13th century and there is every reason to believe that it was established there before it took root in Malacca. The Commentaries of Alboquerque for instance represent the Malacca Raja Xaquendarsa as a Hindu who became Muhammadan on marrying a daughter of the King of Pasai, and indicate that Malacca was regarded in Alboquerque's time as a younger state than Pasai.

x

The conversion of Pasai is moreover related in the Sejarah Melayu before that of Malacca and in fact the whole of the chapters of the Pasai story in that work give one the impression that the events they relate preceded the foundation of Malacca for they are inserted as an episode after the mention of the birth of the last Singapore Raja and before the account of the fall of that town, an event which tradition connects closely with the subsequent foundation of Malacca.

The successor of Ibn Ratuta's friend Malik-al-Dhahir was according to the Sejarah Melayu his son Ahmad. The Pasei Chronicle makes Ahmad a grandson, inserting a generation between him and Malik-al-Dhahir. But the matter is of no importance beside the fact that according to the Pasei Chronicle Ahmad was the Raja in whose time Pasei, Jambi and Palembang were taken by the Javanese of Majapahit. The Chinese account of Palembang, as translated by Groeneveldt, fixes the conquest of that state at about the year 1377, and the Pasei Chronicle goes on to relate that about the same time In 1252 Majapahit was probably, not yet founded, a point which also tells against the ordinary chronology, though as Crawfurd says it is not decisive, as the name may be loosely used for Eastern Java generally.Majapahit took Rangka, Lingga, Riau and Ujong Tanah (the well-known 16th century name of Johor) as well as a number of other places, and made an attempt on Minangkabau by way of the Jambi River.

This then, we may with some probability conclude, was the course of events, which, involving, as it did, the breaking up of the old island state or empire of Singapore by a real, historical expansion of the Javanese power, actually led to the foundation and subsequent development of the new commercial emporium, Malacca. But if so, we must revise our received chronology. The foundation of Malacca instead of being laid in 1252 must

be put at least 125 years later, and the establishment of the Muhammadan religion there would then precede by only a few years the end of the DeCouto, I know not on what authority, gives the date as 1388 and agrees with the Sejarah Melayu in styling the first converted Raja Muhammad. Including him, he speaks of 5 Rajas down to the Portuguese conquest. (Crawfurd, Diet., 1. c.)14th century, instead of taking place about the end of the 13th as is generally supposed.

To this conclusion all the facts here adduced would seem to point, and considering that the opposite view rests only on untrustworthy figures deduced from native chronicles and inconsistent with the main facts contained in those same chronicles, probably it will be generally admitted that the weight of evidence is very strongly in its favour.

To sum up, from the considerations here brought together it seems to follow:

- That during the 15th century and up to the Portuguese conquest 5 or 6 Rajas reigned in Malacca.

- That the last 4 Rajas mentioned in the Sejarah Melayu are undoubtedly historical but that their reigns fall well within this period and cannot be extended to the lengths which the Malay author would give them.

- That the next 2 or 3 Rajas are more or less doubtful and all the earlier ones merely legendary and that the Malay chronology is unworthy of credit.

- That the foundation of Malacca probably and its importance as an emporium of trade in these seas certainly cannot be put back earlier than the beginning of the last quarter of the 14th century, and that the establishment of Muhammadanism as a state religion on the western coast of the Peninsula must be referred to the same period.

Comments