Batu 3, Batu 15, and Yap Ah Loy

The foundation of much of the Federal Highway as we know today (from the old fort of Raja Mahadi to present-day Pantai Valley) is the result of many years (1875 - 1879) of British administrative planning and series of contractual works undertaken by Captain Yap Ah Loy and his Hakka laborers.

On a August Monday afternoon in 1875, the 25-year-old Swettenham arrived at the Klang Residency. There, he found J. G. Davidson working alone, aided by a few assistants, deeply absorbed in surveying and marking out the outline of the Damansara-Kuala Lumpur road.

Swenttenham had naturally expected the presence of both Tunku Kudin and Syed Zin at this important moment in Selangor. And was disappointed when he found they were not there. Fast forward 2,500 days to 8 May 1882, we cut the scene to 1 Savile Row, London.

Here, in an evening meeting organized by the Royal Geographical Society, Yap Ah Loy's name was briefly mentioned outside Selangor for the first time, three years before his untimely death in April 1885. The presenter, Dominick D. Daly, an acquaintance of the Captain China, boastfully recounted, the transformation of Damansara-Kuala Lumpur Road to the audience3:

. . . since the British protectorate was established in Sĕlangor, this track has been transformed into a fair country road, fit for carriage traffic. It is overshadowed by magnificent timber, and plantations of tobacco, tapioca, and rice-fields have been opened. At the time when I surveyed this track, it was considered unsafe for wayfarers, as gang robberies were rife, and man-eating tigers infested the jungle. Since the road was made these evils have vanished, and travelings more secure than in many more civilised countries . . . The town of Kwala Lumpur, in 1875, was under the local administrator of a Chinaman, Yap Ah Loi, known as the Capitan China, to whose enterprise and energy were due its progress and good order . . .

A rather different take on the fair country road described by Daly in 1882, however, can be gleaned from the following evaluation by Gullick (2000):1

. . . when Swettenham became Resident, late in 1882, the Damansara Road was virtually complete, the product of six years intermittent construction. However it was already apparent that this first attempt to provide an alternative to the Klang River as a link with the cast was of little use. As a track for traveller on foot or on horseback it was better than jungle path, but vehicles, in particular bullock carts, cut up the surface and so maintenance costs were prohibitive . . .

We know the last section of the road (present-day University of Malaya area to Market Square) was completed by Yap Ah Loy in November 1879 and it is reasonable to suppose the last segment (and all earlier segments) of the road was built according to the tight specification outlined in the contract. The lack of traffic on the first paved road in Selangor was likely due to its poor maintenance, which left it in a condition difficult to use or travel on by carriage. The lack of maintenance of important infrastructures was related to lack of budget in the colonial government. Curiously it also highlights an important point in the interaction and business relationship between the Residency and Yap Ah Loy. The Captain China was providing paid services to the Residency and would only perform the duties specified in the contract issued by the government.

- F. A. Swettenham, P. L. Burns (ed.) (1970). See p. 278. The diary entry on 16 August 1875 reads:

“ . . . reached Klang at 4 pm and went to the Residency, where I found Davidson, Tunku Kudin, and Syed Zin are I am sorry to say away. They are marking out the Damansara-Qualla Lumpor Road. Davidson has been putting the Klang roads to rights and the place looks much better than it did some months ago . . . ”

On 17 August 1875, he wrote:

“ . . . there are 3 jungle roads we are very anxious to make, one from Klang to Damansara, one from Klang to Selangor, and one from Klang to Langat. They can't however be done without money . . . ”

After the war, Tunku Kudin, the husband of Princess Nuṭfah and the son-in-law of Sultan Abd al-Samad, took control of the fort of Raja Mahadi راج مهادي bin Raja Sulaiman bin Sultan Muhammad Shah (d. 1882). It was later used as a temporary British Residency when Davidson first arrived in Klang in February 1875.

- Swettenham, on the other hand, decided to completely omit the name of Yap Ah Loy in his official account of the history of Selangor. See for example, Swettenham (1907) British Malaya; an account of the origin and progress of British influence in Malaya, John Lane The Bodley Head, London. And this has frustrated Middlebrook and prompted him to research (in the 1930s) about the life of the Captain.

- J. M. Gullick (2000) A history of Kuala Lumpur 1857-1939, MBRAS, Kuala Lumpur.

- D. D. Daly (1882) Surveys and explorations in the native states of the Malayan Peninsula, 1875-82, Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society and Monthly Record of Geography, 4(7) (July 1882), pp. 393-412. Daly's ex-boss, Sir Andrew Clarke, was among the audience.

- The Damansara-Kuala Lumpur road is likely built within 4 years (1876, 1877, 1878, 1879) since we now know that the last 4 miles of the Damansara-Kuala Lumpur road was completed by Yap Ah Loy in November 1879 and the construction work was still in planning stage in August 1875.

- The length of Yap Ah Loy Street is approximately 70 meter. In the following poem by Lín Yóuchuān 林游川 (b. 1953, d. 2007), he incorrectly asserted that the length of the road is 40 yard (36.6 meter).

辛辛苦苦走了幾百年

才來到葉亞來街

卻只剩下尷尬的四十碼長

一邊是馬來西亞銀行

一邊是復盛當

短短的一小截盲腸

延續着一大段歷史的百結愁腸

在吉隆坡繁華的體內

人家不除不快

是我的傷

我捧着這截盲腸在街頭彷徨

不知道該向銀行舉借

還是向當鋪典當

The poem conveys a profound sense of loss and disillusionment over the transformation of Yap Ah Loy Street, once a symbol of history and cultural legacy. By using the word 剩, the author mistakenly assumes that the street was originally longer, but over time, it was reduced to a short and neglected alley. By positioning himself as a crippled soul in modern Kuala Lumpur, he reveals the inner conflict of someone who feels a personal connection to a place that has been overtaken by commercial progress. The juxtaposition of Maybank and Fook Sang Pawnshop — representing financial and transactional spaces — highlights the perceived commodification of heritage, making him feel metaphorically trapped between borrowing or pawning, symbols of survival rather than celebration.

In describing the street as a gut full of sorrow, the author feels as though this erasure of history is personal, amplifying a sense of helplessness as he watches a space of cultural importance become an expendable fragment. By framing his thoughts this way, he emphasizes a feeling of powerlessness, as though history has been unfairly diminished by forces beyond his control. Through the metaphor of the wound, the author portrays himself as someone hurt and displaced by the relentless march of development, which neglects the emotional and historical weight of places like Yap Ah Loy Street.

See Tang Ah Chai 陳亞才 (2016) 葉亞來相遇吉隆坡, p. 114. In p. 115, in a note likely appended by Tang, we were told that the length of the road is less than 50 meter: 葉亞來街口:左邊是馬來亞銀行,右邊是當舖,整條街長度不超過五十公尺。In p. 116, we were given another estimate by Tóng Mǐnwēi 童敏薇. Her value is even lower than the values quoted by Lin and Tang. Tong's value is the most ridiculous, at only 30 yards (27.4 meter). It is puzzling why these authors were unable to get their basic fact right since the length of Yap Ah Loy Street can be obtained easily.

1957/0000779W

Specification for completion of Damansarah Road by contract

with the Captain China (18 February 1879)

I, Yap Ha Loy, Captain China, residing at Qualla Lumpoor hereby agree and undertake to form and construct a road near Qualla Lumpoor, subject to the approval of the Superintendent of Public Works or other authorised officer on the following terms and specification.

- The Road to commence from the finished portion at Anak Ayer Batu and to extend thence to Qualla Lumpoor a distance of about 3½ miles.

- The jungle to be cleared to a width of 20 feet on either side of the drain, the road to be 26 feet wide, exclusive of the drains. Drains on each side of road 3 feet wide and 2 feet deep each on high land, but to be 4 feet wide on wet lands.

- Gradients of road not to exceed 10%.

- Metalling to be 6 inches thick of laterite and laid as per sketch for a width of 14 feet in the centre of the road, the crown of the road to be 14 inches, higher than the sides. The metal to be laid in two layers of 3 inches thick each, each layer to be rolled separately till it is properly consolidated.

James C. Jackson (1963) Kuala Lumpur in the 1880's: The contribution of Bloomfield Douglas, Journal of Southeast Asian History 4(2), p. 120.

- All roots, stumps, and wood to be grubbed out, and holes properly filled in, (?) at least 6 inches, above natural surface to allow for subsidence.

- The lines of road to be followed as they are laid out by the Superintendent of Public Works or his officers.

- The Government will supply as many carts and cattle as can be spared, to be replaced of, damaged or killed, but the contractor will find his own tools, plant, etc.

- Bridges and culverts to be made wherever the Superintendent of Public Works may direct, according to the plan in the Survey Office and to be of pataling, tumboosou, mirbow or biliong or equally durable woods for their respective parts, the approaches to be completed with metal.

- No cash payments will be made on account of this work but the work, if properly carried out according to the specifications, and to the satisfaction of the Superintendent of Public Works, will be valued at the rate of $3,000 per mile. The whole amount bring placed to the credit of the Captain China with the Selangor Treasury to liquidate a portion of his debt to the Selangor Government.

- The work to be completed in the right months, subject to a fine of $10 a day for many day, after the expiration of the contract. [This clause was cancelled by Douglas]

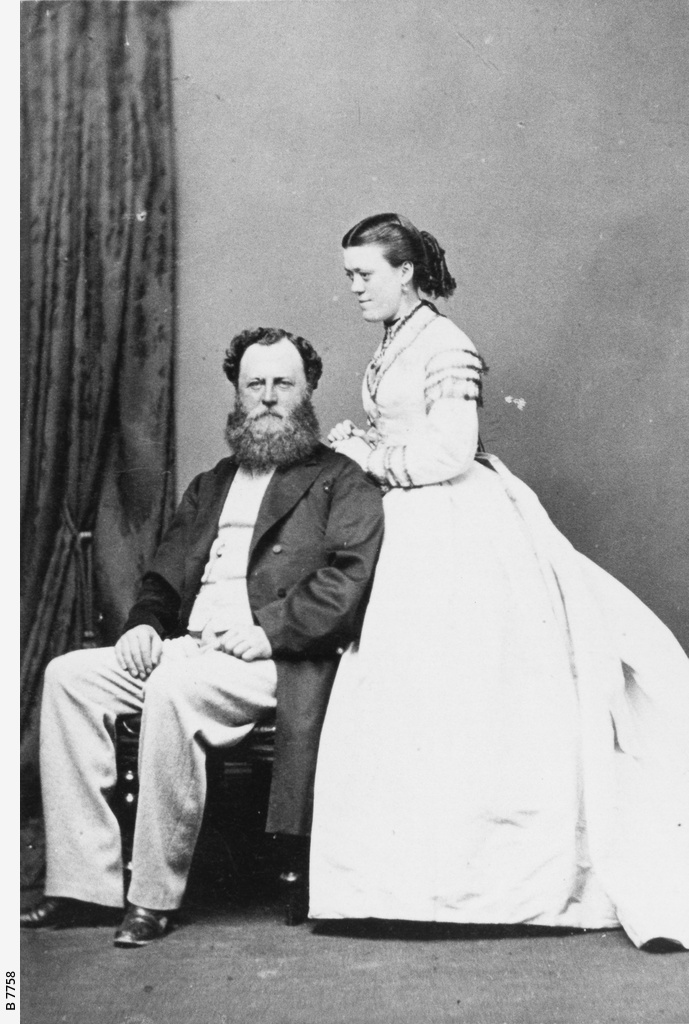

The following exchanges were written by Bloomfield Douglas, R. N. R. = Royal Naval ReserveR. N. R. (b. 1822, d. 1906) and his son-in-law, Dominick Daniel Daly (b. 1844? d. 1889). Daly married Douglas's eldest daughter, Harriet Willie Douglas (b. 1851, d. 1927) in 1871 when they were both in Australia.

Douglas was initially, in April 1874, given the assignment to go to Singapore to recruit Chinese miners for the mines in Northern Territory. Unaware of his bad employment history in Australia (that Douglas was asked to resigned in 1873), the Colonial Office in Singapore made the ill-judged decision to employ Douglas as acting police magistrate (October 1874) and second police magistrate (May 1875). In December 1875, Douglas was transferred to Langat, Selangor, to replace F. A. Swettenham as the assistant to J. G. Davidson. In April 1876, Davidson was transferred to Perak, Douglas was made acting Resident of Selangor.

D. D. Daly, Esq,

Central District Magistrate and Superintendent of Mines, Kuala Lumpur,

I have the honor to request, that you will take a convenient opportunity to inspect the work done by the Captain China, on the Kuala Lumpur Damansarah Road, and report on or before the 20 December, as to the value of the work done in order that it may be written off the Captain China's debt to the State, and the amount to (be) credited to him, entered as amongst miscellaneous receipts in the revenue accounts. I shall be glad if you will report generally on the work done by the Captain China.

I have the honor to be, Sir,

Your most obedient servant, Bloomfield Douglas,

H. B. M's Resident Selangor, British Resident's Office, Klang, Selangor. 8 November 1879.

H. B. M. Resident,

The total distance of Road formation made by the Captain China on the Damarsarah and Quala Lumpur Road is 4 miles and 41 links, of which 31 chains and 70 links are metalled with laterite. The bridges are temporary structure and the Captain's woodcutters are engaged cutting up good timber for the permanent bridges. I value the work as follows, viz 4 miles Road formation with temporary bridges at $1,300 a mile ($5,200), 31 chains of laterite metaling at $600 a mile ($229.40). Total valuation $5,429.40.

D. D. Daly,

Central District Magistrate, Kuala Lumpur, 13 December 1879.

Comments