How Amalaka the Fruit was cancelled in Malay history

To fully appreciate the events leading to the cancellation of Malaka the Fruit, we must first roll our clock back to medieval Melaka.

Enter the first paragraph of Eredia's Description of Malacca (1613):

Malaca significa Mirabolanos, fructa de hua arvore plantada ao longo de hum ribeiro chamdo Aerlele, que dece das fontes do outeyro de Buquet China pera o mar, daquella costa de terra firma de Viontana . . .

This long-forgotten literary gem was written by a Bugis-Portuguese muggle when he was 50-year-old. It is jammed with data so valuable it is practically the vip area of Melaka's history.

First things first

Before we attempt to e.g. ChatGPT: “Malaca means Mirabelle plums, fruit from a tree planted along a stream called Aerlele, which descends from the sources of the Buquet China hill to the sea, along that coast of mainland Viontana . . ."crack open Eredia's time-travel safe with large language models, we should perhaps, run some old school literature review.

And our first stop? J. V. G. Mills (1887 - 1987), a former High Court Judge in the Straits Settlements.

J. V. G. Mills' translation (1930) of this passage

Malaca means Myrobalans, the fruit of a tree growing along the banks of a river called the Aerlele, which flows down from its source on the hill of Buquet China to the sea, on the coast of the mainland of Ujontana.

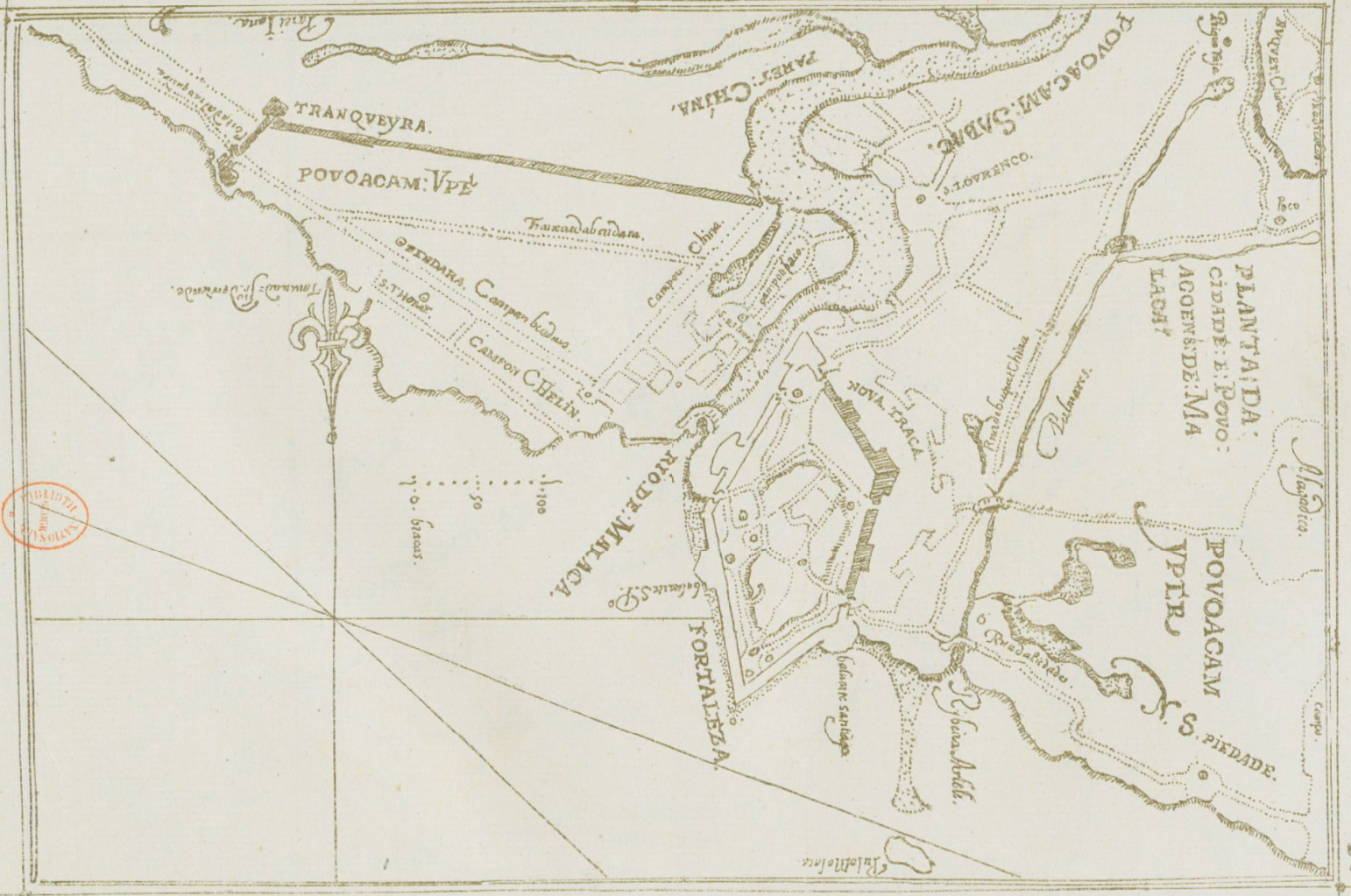

is classy but a tad challenging for the modern brain because Eredia's toponyms (see Figure 1) are kept in their archaic forms. For the benefits of modern readers, let me renovate Mill's text with relatable place names and the good old Linnaean binomial name (which we will talk about later).

Malaca signifies Myrobolano emblica, fruits of a tree growing along the bank of a small stream called Ayer Leleh, which flows from Bukit Cina to the sea (Strait of Melaka), on the coast of Thai-Malay peninsula (Ujong Tanah).

Since Eredia spent his childhood in Melaka, it is not unreasonably to suppose that the young Eredia must have seen the Mirabolanos trees and probably also tasted the fruit. Note that the fruit of Malaka was mentioned instead of the tree of Malaka, which is probably an indication that the local population appreciated the medicinal properties of the fruit (more to come).

Furthermore, Eredia was not merely repeating the phoneme /malaka/ but instead he matched it with a Latin word from Greek = μύρον + βάλανος = Scented + acorn./mirabolanos/, a sister species. In the book, he depicted Ribeiro de Airlele as a small stream flowing from Bukit Cina to the Strait of Melaka. The now extinct Air Leleh stream, used to broad enough to justify the construction of bridges. Eredia's reference to Air Leleh gives us a clue that the Malaka trees were grown or cultivated only in specific locales (and not everywhere). It was probably an imported plant and not naturally occuring species.

Tome Pires, who wrote Suma Orientalis, nearly 100 years before Eredia, mentioned that the orang selat visited Parameswara with a fruit basket and the king was reported to have said:

you already know that in our language a man who runs away is called a Malayo, and since you bring such fruit to me who have fled, let this place be called Malaqa, which means ‘hidden fugitive' . . .

One can readily understand why Pires's account (as told to him by the Javanese, who was probably not Malay-friendly at the time when Pires interviewed them) was not fully adopted in Sejarah Melayu. The Javanese were obviously joking derogatorily when they associate malayo with fleeing, but Pires entered the half-joke in his book anyway.

Apparently Malaka (ملاک) made many appearances in Sejarah Melayu (see Figure 2, Raffles MS18, now in the library of Royal Asiatic Society). But the plot takes a twist – forget the fruit focus, now we are zooming in on the tree where the king stood, witnessing a royal dog getting the boot from an albino mousedeer.

Why the shift, you ask? Well, apparently the original emphasis on fruit was causing a storytelling traffic jam. So, they decided to flip the script, maybe borrowed a page from some folktales from Acheh or Sri Lanka (which we will also discuss later), and landed on this quirky tree-kicking scenario.

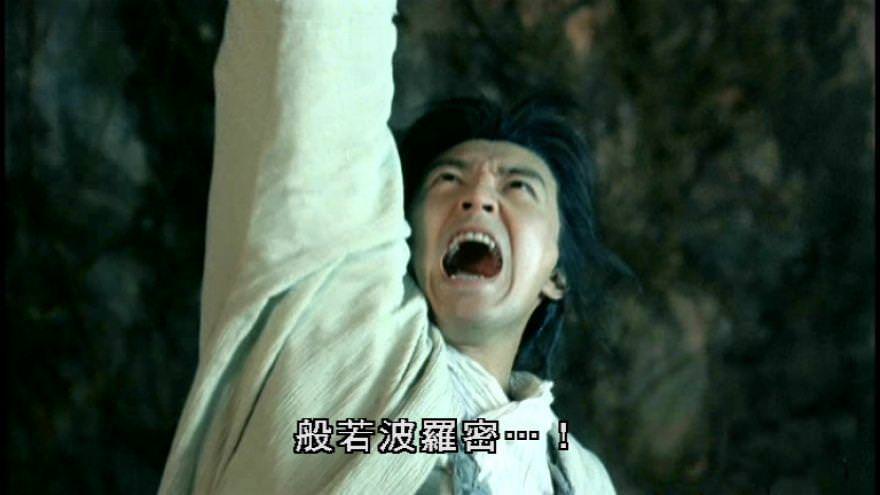

Interestingly, the same fruit has also had a notable mention in Chinese literature, thanks to a reference by the remarkable Chinese monk Tang Xuanzang (602 - 664) 唐玄奘, in his renowned work Great Tang Records on the Western Regions 大唐西域記. It is like this fruit got its own feature in the Chinese action movie!

阿摩落迦 ,印度药果之名也 。

Teaming up with haritaka 訶梨 and bibhitaka 毗梨, this power trio goes by the name triphala (三果 or 三勒, see Figure 3) in the realms of Buddhism and Ayurveda.

Alright, so the name amalaka is probably of Bollywood origin, considering how it's the rockstar of fruits in Indian culture. If we're playing fruit detectives, breaking down amalaka is like decoding a spicy masala recipe – it is a-mala (a = without + mala = impurity) and ka (fruit). And guess what? The other two Triphala gang members are in on the deconstruction party too: Harita (green) + ka, and bibhita (fearless) + ka.

Given that amalaka is a bit of an exotic word outside Indian circles, it has undergone some serious makeovers in non-Indian cultures (see Figure 4).

$$ \begin{vmatrix} \textrm{Æ}\\ \textrm{M}\\ \textrm{L}\\ \textrm{K} \end{vmatrix} \approx \begin{vmatrix} \textrm{e}\\ \textrm{mb}\\ \textrm{li}\\ \textrm{ca} \end{vmatrix} \approx \begin{vmatrix} \textrm{a}\\ \textrm{m}\\ \textrm{la}\\ \textrm{ki} \end{vmatrix} \approx \begin{vmatrix} \textrm{a}\\ \textrm{m}\\ \textrm{la}\\ \textrm{ka} \end{vmatrix} \approx \begin{vmatrix} {\scriptsize\textrm{阿}}\\ {\scriptsize\textrm{摩}}\\ {\scriptsize\textrm{落}}\\ {\scriptsize\textrm{迦}} \end{vmatrix} \approx \begin{vmatrix} \textrm{a}\\ \textrm{m}\\ \textrm{la}\\ \textrm{} \end{vmatrix} \approx \begin{vmatrix} {\scriptsize\textrm{菴}}\\ {\scriptsize\textrm{沒}}\\ {\scriptsize\textrm{羅}}\\ {\scriptsize\textrm{}} \end{vmatrix} \approx \begin{vmatrix} \textrm{}\\ \textrm{ma}\\ \textrm{la}\\ \textrm{ka} \end{vmatrix} \approx \begin{vmatrix} \textrm{}\\ \textrm{ba}\\ \textrm{la}\\ \textrm{kka} \end{vmatrix} $$Now, here's where it gets juicy – Ng (2011) drops the bomb that Carl Linnaeus was responsible for turning amalaka into the fancier emblica in his Species Plantarum (1753). Ng is clearly vibing on a misinformation track because Linnaeus was just recycling Bauhin's “emblica" and Zanorii's “nellika" (Tamil, nelli = நெல்லி, see Figure 5).

The fact that Ng is dancing to the wrong botanical beat can be strengthened further if a dictionary is consulted. The lowdown from the 20-volume Oxford English Dictionary (see Figure 6) spills the tea – the use of emblicos | emblick was rocking the English speaking scene even before Bauhin jumped on the bandwagon.

Forms: 6 emblico, 7 emblick.

[ad. med.L. emblica, -icus, ad. Ar. amlaj a. Pers. āmleh, cf. Skr. āmalaka of same meaning.]

The fruit of Emblica officinalis, a tree of the family Euphorbiaceæ, whose flowers are aperient, leaves and bark a remedy against dysentery. Also emblic myrobalan.

- 1555 Eden Decades W. Ind. iii. iv. (Arb.) 151 Mirobalanes‥which the phisitians caule Emblicos and Chebulos.

- 1678 Salmon Lond. Disp. 136/2 The five sorts of Myrobolans‥the Emblick purge Flegm and Water.

- 1708 Motteux Rabelais ii. xiv, A Boxfull of conserves, of round Myrabolan plums, called Emblicks.

- 1811 Hooper Med. Dict., The emblic Myrobalan is of a dark blackish grey colour.

. . . before anybody questions whether I am qualified to change history, let me explain that my comments are based on botany, and I am, after all, a qualified taxonomic botanist, one who deals with the naming and classification of plants . . .

Francis Ng (2011) What tree did Parameswara really see in Malacca? Star BizWeek 5 November 2011, p. 23.

But wait, the taxonomy maestro, shakes things up further by dropping another axiomatically correct but historically incorrect bomb: the tree seen by Parameswara was not Phyllanthus emblica, but the cool native kid Phyllanthus pectinatus.

Ng's line of reasoning?

P. pectinatus is the original gangster phyllanthus tree, and P. emblica is the imported Bollywood superstar. And he reminded us that Parameswara's Melaka was not populated by any civilized people before he cut the ribbon and opened the city.

What is the probability of native people of Melaka growing and cultivating a foreign drug-tree before Parameswara civilized the land? Probably zero, according to Ng.

But hold on. Because Ng's probability can be easily made nonzero! It can be immediately rendered weaker if we can show that the romantic pelanduk tale is just a second-hand love story, swiped right from Hikayat Raja Pasai or some wild Ceylon folktale.

| Pasai | Melaka | Kandy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hero | Mĕurah Silo | Parameswara | An unnamed Basket-mender |

| Etymon | Pasai the Dog | Mlak ملاک the Tree | Tranquility the Rock |

| Attacker | Mouse deer | Rabbit | |

| Attackee | Pasai the Dog | Unnamed dog | |

But why stop there when we can manufacture a whole new romantic saga for the origin of the placename? Imagine this: Parameswara's advisors, decked out in ancient cupid gear, decide to name the place after the swoon-worthy amalaka because, you know, it is practically something they associate with the gods they worshipped. In Malay/Indonesian language, the base of the fruit-shaped dome found on top of Indian temples is also called amalaka:

noun. Architecture. hiasan puncak di bawah mahkota berbentuk piringan batu pada menara utama bangunan candi Hindu yang menyerupai teratai (sebagai singgahsana untuk dewa) atau melambangkan matahari (sebagai pintu gerbang ke syurga)

It is clearly an auspicious name since it is a throne for the deities (singgahsana untuk dewa) or the gateway to heaven (pintu gerbang ke syurga).

Comments