“Pagar makan padi" in early publications and manuscripts

The Malay phrase pāgar mākan pādi or

ڤاڬر ماكن ڤاديcan be found in R. J. Wilkinson's Malay-English Dictionary. On p. 449, Wilkinson wrote:

ڤاڬر pagar.Even though the example given (in a business context) is rather odd (since the phrase pāgar mākan pādi is normally used when trust is betrayedSee Abdullah Hassan's Kamus Istimewa Peribahasa Melayu (2nd ed.) for example. Entry 2930: Padi makan padi (= tanaman). Orang yang kita percayai berkhianat kepada kita, in , p. 160. Cross-references are made to Entries 2939, 3735, 3996, and 4217, which are (a) Pancing makan umpan (p. 160); (b) Sokong membawa rebah (p. 201); (c) Telunjuk mencocok (= merosok, menikam) mata (p. 214); (d) Tongkat membawa rebah (p. 225).),

A fence; a palissade; a row of stakes or palings.

Pagar makan padi: the fence eats up the padi;

the precautions for diminishing loss eat up the profit. . .

It is spelt with consonant p, long vowel ā, consonant g, and consonant r. So strictly speaking it ought to be pāgar and not pagar (and definitely not pĕgar, as asserted by the revisionists). Also, the short vowel a between g and r is not explicitly shown, it shows that the Arabic diacritical mark for short vowel a, Fatha َ◌, is not consistently employed in the Jawi spelling scheme.

The similar phrase (rendered as old Dutch spelling as: pagar djoega mĕmakan padi) can also in a Dutch papersee H. C. Klinkert (1866) Eenige Maleische spreekwoorden en spreeekwijzen, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde van Nederlandsch-Indië 13de Deel, [3e Volgreeks, 1e Deel], p. 40 and p. 58. published by H. C. Klinkert in 1866.

. . .All the officers of the court hate Hang Tuah and tells Pateh Kerma Wijaya he is “a fence eating the crop", an officer of the court who seduces the Raja's concubines. . .

For the full narrative of the story, we can consult Muhammad Haji Salleh's English translation of Hikayat Hang Tuah, which he published in 2010. Prof. Muhammad's translation on pp. 315 - 316 is reproduced as follows:

When they concluded their meeting, all the officials and loards proceeded to Patih Kerma Wijaya's residence. On their arrival, all of them cast their headdresses and keris down before him. His attention caught by this sudden demonstration.Patih Kerma Wijaya then regurgitated the same complaints to the Sultan of Melaka, on p. 317:

Patih Kerma Wijaya asked: “Why are you all behaving in this manner My Lords? What is the reason for this?"

All the officials and lords replied, “What is the use of us being appointed officials, My Lord, when somebody commits an outrage in the palace and we stand there unable to act? Should thtere be any enemies now, surely we are they? What is the use of use standing guard day and night under His Majesty? What we have witnessed is as summed up in the proverbs of the Malays: The fence has devoured the crop. Event though we wish to bring our grievances to the ears of His Majesty, he will not listen to use; if we were to keep silent, tomorrow or the day after we shall bear this shame; so we have made it our resolve to inform Kiai Patih, for the Kiai is a great minister. As long as My Lord is aware of this matter, then at least you can bear witness to us."

As soon as he heard their grievances, Patih Kerma Wijaya asked, “Who dares to bring shame on this palace?"

They replied, “Who else greater than Hang Tuah who would dare commit such an act? Last night we were on guard in the courtyard of the palace it was then that we saw Hang Tuah talking to and flirting with a beloved concubine of His Majesty; we wanted to slay him at that very moment, but we were afraid that we would be found guilty by His Majesty, for Duli Yang Dipertuan loves him dearly and has bestowed countless gifts on him, and we may be thought to be envious of him."

The Patih bowed and said, “I bring Your Majesty words of treason. What is the use of us continuing to serve as your officials? One mere individual commits an outrage, and we are not able to kill; how shall we ever defeat Your Majesty's enemies and foes, as the adage of the Malays says, “The fence has devoured the crops!"However, the phrase was uttered only once, and it was used by Patih Kerma Wijaya, in p. 248 (Chapter 9: Hang Tuha bersuaka di Inderapura dan memikat Tun Teja) of Ahmat Adam's recent transliteration (based on Manuscript 23, University of Malaya Library. See also Or. 16215 in the British Library. Both the British Library copy (dated between 1828 to 1835) and the University of Malay Library copy are derived from the same parent manuscript):

The Raja demanded greater clarification, “What do you mean, My Lord?"

Patih Kerma Wijaya replied, “O My Lord, last night we were on guard in the courtyards; there we saw a woman from the palace with the Laksamana. Your servants wanted to kill him, but we feared to do Your Majesty wrong, for Your Majesty places your entire trust in him; moreover he is chief over all of us."

. . . sekalian ke bawah Duli Yang Dipertuan. Hendak patik persembahkan pun patik takut kata orang banyak ke bawah Duli Yang Dipertuan. “Lihatlah Patih Karma Wijaya dengki akan seorang hamba Raja, melihat Duli Yang Dipertuan sangat kasih akan hambanya itu." Maka sebab itulah patik tiada berani berdatang sembah. Akan sekarang adalah seperti pantun orang, ‘pagar makan padi.'"

Setelah Raja Melaka mendengar Patih Karma Wijaya demikian itu, maka Raja pun terkejut seraya bertitah, “Si Tuhakah berbuat cabul akan kita?" Maka sembah Patih Karma Wijaya, “Hang Tuhalah Tuanku, bermain-main di dalam istana Duli Yang Dipertuan intu. Selama patik sudah lihat, patik hendak persembahkan patik takut." Maka sahut segala pengawai yang disembah Patih Karma Wijaya itu, “Sungguh Tuanku; ada patik melihat Hang Tuha itu berkata-kata dengan seorang perempuan di dalam istana Duli . . .

The same phrase is repeated twice in separate chapter (Chapter 14: Marga Paksa Tujuh Bersaudara Berada di Melaka, p. 380). This time, the sequence is similar to the narrative given by Muhammad Haji Salleh, i.e. first by the court officers to Patih Kerma Wijaya, then Patih Kerma Wijaya repeated the complaint to the Sultan of Melaka.

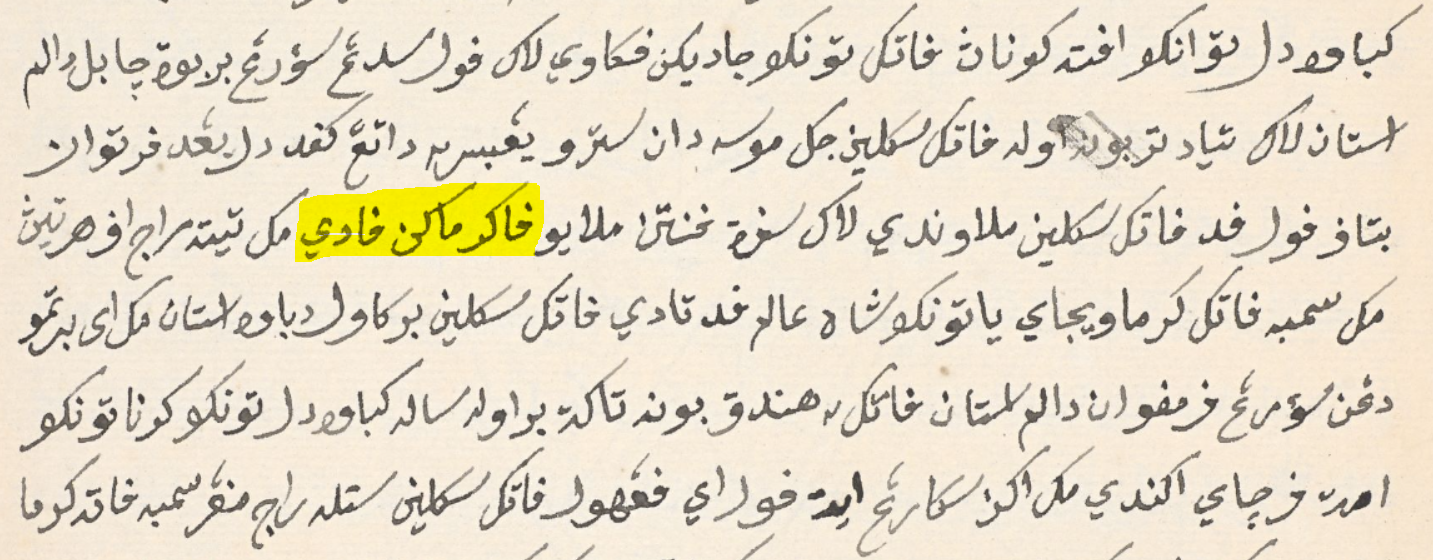

I do not have access to Manuscript 23 but the sister copy of the University of Library manuscript can be accessed easily since it has been digitized by the British Library, and the relevant passage is shown below:The phrase ڤاڬر ماكن ڤادي (pagar makan padi) is highlighted in yellow.

The phrase ڤاڬر ماكن ڤادي (pagar makan padi) is highlighted in yellow. The roman transliteration for the passage illustrated is given by Ahmat AdamAhmat Adam (2018) Hikayat Hang Tuha (atau Hikayat Hang Tua), SIRD, Petaling Jaya, p. 380. as follows:

“. . . di dalam istana lagi tiadakan terbunuh oleh hamba sekalian? Jika musuh yang lain berapa lagi? Apatah gunanya hamba duduk terkawal siang dan malam di bawah Duli Yang Dipertuan ini? Seperti pantun Melayu, ‘pagar makan padi' itu adalah hamba sekalian lihat. Hendak pun hamba sekalian persembahkan ke bawah Duli Yang Dipertuan tiada akan didengarkannya. Hendak pun sahaya diamkan kalau-kalau kemudian harinya hamba sekalian beroleh malu. Itulah dimaklumkan pada kyayi. Maka tuan pun menteri besar juga; lamun sudah kyayi tahu pun padalah saksi hamba sekalian ini." Apabila Patih Karma Wijaya mendengar kata segala kata segala pengawai itu, maka kata Patih Karma . . .

The phrase ڤاڬر ماكن ڤادي (pagar makan padi) is highlighted in yellow. The roman transliteration for the passage illustrated is: . . . (seperti pantun Melayu) pagar makan padi (maka titah raja) . . .

Comments